by Anne Lindsay

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

University of Manitoba

|

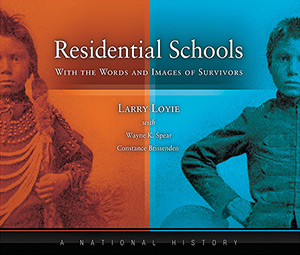

Larry Loyie with Wayne K. Spear and Constance Brissenden, Residential Schools with the Words and Images of Survivors – A National Story. Indigenous Education Press, 2014, 112 pages. ISBN 978-0-9939-3710-1, $34.95 (hardcover)

A beautifully illustrated and skilfully arranged book, Residential Schools: With the Words and Images of Survivors, by residential school survivor Larry Loyie, offers a very approachable introduction to understanding the Indian Residential School System as it existed in Canada. A rich combination of images and the words of survivors are stitched together by the threads of Loyie’s narrative. The inclusion of a map, a timeline, and a glossary at the end of the book add to this format and invite the reader to engage with the material.

A beautifully illustrated and skilfully arranged book, Residential Schools: With the Words and Images of Survivors, by residential school survivor Larry Loyie, offers a very approachable introduction to understanding the Indian Residential School System as it existed in Canada. A rich combination of images and the words of survivors are stitched together by the threads of Loyie’s narrative. The inclusion of a map, a timeline, and a glossary at the end of the book add to this format and invite the reader to engage with the material.

Loyie’s skilful telling of the story of the residential schools in Canada through the eyes of survivors like himself allows the reader to understand the impact of the system at a personal level. Loyie tells the reader that at age 13 he “felt joy to be released from the prison-like school. I had wanted to get a good education. This didn’t happen, as most of the teachers were not trained. I did have one educated teacher, Sister Theresa, who inspired me to continue learning. I am grateful to her” (pp.4–5).

This first person engagement with the topic is a real strength, allowing the reader to connect to the material through the feelings students experienced at the schools and encouraging a deeper understanding of the lived experiences of students. Also interesting is Loyie’s positioning of the importance of the conversation around residential schools as part of guaranteeing the human rights of all children, a seldom discussed but important connection worthy of greater exploration.

Loyie begins his exploration of the residential schools system by positioning it as part of a larger colonial appetite for land that emerged on the Canadian prairies during the 19th century (enter John A. Macdonald, and a series of policies including the reserve system and the industrial school model). Initially explored in the United States, it was not long before Canada was looking south of the border for ways to assimilate Indigenous people, and to the Roman Catholic, Methodist (and later United), Presbyterian, and Anglican Churches for the design and operation of schools for help with this. Soon schools were quickly (and inexpensively) constructed, and children moved into them to forward the goal of forced assimilation and increased settler access to land.

While much of the historical material included in this book is not new, it is presented in a very readable prose, and skilfully interwoven with definitions of terms and with side bars that introduce related material. But its real strength lies in the author’s ability to provide the reader with a sense of seeing the schools through a student’s eyes. Combining text, images, first person accounts, and impressive design, sections like “Looking at School” distinguish this book from most others on the subject.

Where Chapter 1 sets the foundation and tone for the rest of the book, Chapter 2 discusses “the meaning of culture and traditions.” Covering not only “ten thousand years of culture,” but also a vast geography, and practices from potlatch through storytelling, to wampum belts and dance, Chapter 2 offers a beautifully presented celebration of the richness and diversity of Indigenous society.

Chapter 3 explores the children’s experience of leaving home, the coercion used against parents to encourage them to send them to the schools, and the real threat of force from the police. As Fred Francis Willier recalled, “My parents received a letter from the Indian Agent telling them if I didn’t go to school my parents could go to court. They had already suspended the family allowance” (p.33).

This chapter acknowledges the distinct experiences of Inuit, Metis, and First Nations children at the schools, but also outlines their similarities and includes discussion about resistance and power, offering valuable insights to the reader who might wonder how so many people could have been controlled by what might seem to be very few officials.

Chapter 4 explores school life, looking at the staff, the half day system, military discipline, and other facets of school life. Here Shirley Horn’s description of her life at school exemplifies the book’s skilful balance between exploring the residential school system’s coercive and negative aspects and avoiding painting survivors as dimensionless victims. This balance continues in Chapter 5: “The Truth is Heard: The Dark Side of Residential Schools.” Here the voices of students are interwoven with images and text to discuss sanitation, health, and nutritional experiments. The reader is introduced to the sensitive topics of sexual abuse and death, including suicide at the schools. In the context of the epidemic rates of suicide that some Indigenous communities are currently facing, this topic is of particular importance today. Also notable in this chapter is a brief but valuable discussion about how few photographs former students of the schools have of their experiences. Given how many images were captured for various reasons, this paucity of personally held images underlines the distinctly institutional nature of this experience of childhood.

Following that difficult chapter, Chapter 6: “Friendship and Laughter: Coping with a New Life” offers yet another reminder of the strength and resilience many children brought with them from their homes. Here sports like hockey, artistic expression, romance and marriage, and the skilful use of humour and laughter remind the reader that resistance can come in many forms.

Chapter 7 discusses the end of the system and the importance of healing, the close of the schools, the civil rights movement, and Phil Fontaine’s courageous decision to share his own story of abuse publicly. This diverse chapter provides a framework and perhaps an invitation for the reader to consider where they personally fit into the residential schools story, and where they might want to fit into future responses.

Taken as a whole, this book offers a very approachable introduction to the residential schools system, and provides an excellent example of the potential that can be realized by foregrounding personal stories presented in their entirety and without comment, supported by excellent images, careful design, and a respectful and well written text. If it has one failing, it is a tendency to compress time, which is to perhaps miss opportunities to foreground differences in experiences depending on the dates and locations of the school that students attended. But this is a small issue in the context of this work. This book would make an excellent addition to any library and could serve as a particularly helpful resource for educators. It would also be of interest to artists and designers looking for examples of how to present complex and difficult subjects in a respectful and engaging fashion.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 19 November 2021