by Jim Mochoruk,

Department of History, University of North Dakota

|

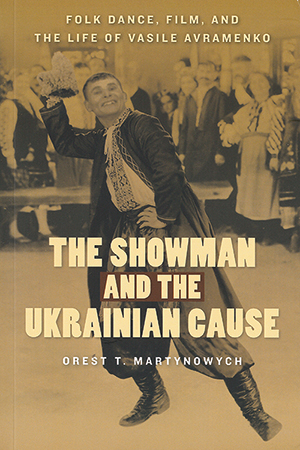

Orest T. Martynowych, The Showman and the Ukrainian Cause: Folk Dance, Film, and the Life of Vasile Avramenko. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2014, 219 pages. ISBN 088755-768-2, $27.95 (paperback)

There is no question that Vasile Avramenko has achieved iconic status within the Ukrainian-Canadian community. (There is a certain irony here, as Avramenko spent the majority of his life in the US and became a citizen of that country—not Canada). Widely regarded as the “father of Ukrainian folk dancing” in North America and the man most responsible for winning widespread mainstream acceptance and praise for Ukrainian folk culture in the 1920s and 1930s, Avramenko has been lionized, eulogized, and memorialized in a whole host of fashions. Indeed, between his work as a dance master and instructor, choreographer, promoter, impresario, and producer of Ukrainian films—and his phenomenal talent for self-promotion—Avramenko was oft-times seen as one of the major voices of the “Ukrainian Cause” in North America; a cause that not only sought to showcase and celebrate Ukrainian culture but which demanded recognition for the right of Ukrainian-speakers to have an autonomous political state in their homeland.

There is no question that Vasile Avramenko has achieved iconic status within the Ukrainian-Canadian community. (There is a certain irony here, as Avramenko spent the majority of his life in the US and became a citizen of that country—not Canada). Widely regarded as the “father of Ukrainian folk dancing” in North America and the man most responsible for winning widespread mainstream acceptance and praise for Ukrainian folk culture in the 1920s and 1930s, Avramenko has been lionized, eulogized, and memorialized in a whole host of fashions. Indeed, between his work as a dance master and instructor, choreographer, promoter, impresario, and producer of Ukrainian films—and his phenomenal talent for self-promotion—Avramenko was oft-times seen as one of the major voices of the “Ukrainian Cause” in North America; a cause that not only sought to showcase and celebrate Ukrainian culture but which demanded recognition for the right of Ukrainian-speakers to have an autonomous political state in their homeland.

Orest Martynowych has set out to utilize Avramenko’s massive personal archive, now housed at the Library and Archives of Canada, as well as a broad array of other archival collections and a host of contemporary newspaper sources to examine Avramenko’s life and work in a fashion that is both critical and entertaining. And make no mistake about it, readers of this brief but densely packed study will be both educated and entertained. Martynowych’s study is a fast-paced, meticulously researched and well-written examination of much more than one man’s life; rather, it is a fascinating series of chapters in the history and politics of eastern European immigrants in North America. Best of all, unlike some of the fawning biographies or synopses of his life produced by contemporary acolytes, or the latter-day hagiography that accompanied the travelling exhibit honouring Avramenko’s life and work (2004-2006), Martynowych’s Avramenko emerges as a fully realized, if deeply flawed, man.

ply flawed, man. Beginning with Avramenko’s profoundly unhappy childhood in the village of Stebliv, his travels to the far east of the Russian Empire, his struggle to become literate, his first encounters with the performing arts and Ukrainian popular culture, and then, most significantly, his experiences of the Great War and the immediate postrevolutionary period (1917–1925), Martynowych manages to tell the reader much about Avramenko and about the geopolitical environment of post-war eastern Europe and the evolution—or perhaps codification and rediscovery would be more appropriate—of the Ukrainian theatre and folk arts tradition. One also sees the essentially orphaned Avramenko finding a home of sorts and something in which to believe: the cause of an independent Ukraine.

After his time with Petliura’s Directory, internment in Polish controlled Galicia, and a sojourn in Czechoslovakia (in every instance Avramenko used his time to hone his knowledge and skill related to Ukrainian dance and folk culture and deepened his determination to use both as propaganda for the cause of an independent Ukraine), Avramenko had emerged as an acknowledged authority on, and practitioner and teacher of, Ukrainian dance. With the help of several supporters he managed to book passage to Canada late in 1925, beginning a crucial new phase in his life.

As Martynowych makes clear, the timing of the arrival of the self-proclaimed “Dance Master” was propitious: the animus against Ukrainians, which had reached a fevered pitch in the Great War and its immediate aftermath, had clearly abated. Moreover, both mainstream Canada and the immigrant generation of Ukrainians were greatly concerned by the popular culture that was taking hold of North America and corrupting the youth. Avramenko’s promotion of healthy, respectable folk culture was seen by many English-speaking commentators as an antidote to the excesses of the jazz age, while for Ukrainian parents the Master’s dance classes and insistence upon immersion in Ukrainian-language and culture were a way of keeping their Canadian-born children tied to their cultural heritage and families.

What is most interesting about the earliest phase of Avramenko’s work in Toronto in 1926, and to a lesser extent in Winnipeg, was that he was willing to work with anyone in the Ukrainian community, including the pro-communist Ukrainian Labor Farmer Temple Association (ULFTA)—a seeming aberration given his strong anti-communist views. (Martynowych believes that this may have been because of Avramenko’s desire to return to Soviet-Ukraine at some point in order revive traditional folk culture there—thus he couldn’t afford to alienate the pro-Communists in Canada). It was in the course of his work in training Ukrainian dancers, establishing schools of dance across mainland Canada and staging well-received public shows and tours between 1926 and 1928 that the legend of Avramenko, and his iconic status in Canada, took hold.

Although some cracks were beginning to emerge in the façade of the Dance Master’s public persona when he left for the larger and greener pastures of the US in 1928 (arrogance, impatience with friends and collaborators, poor business skills, questionable fund-raising methods, and a suspicious closeness to a young dancer), his Canadian reputation was still largely intact – something that would serve him well in the future. Believing that the 1,000,000 strong Ukrainian-American community would provide a better audience for his work, and that the cultural meccas of New York and Hollywood were the places where his talents could be put to their fullest use, he had always intended on going to the US.

Martynowych makes clear that although Avramenko tried to recreate his Canadian success with dance schools, classes, elaborate productions and tours, each and every one of the Dance Master’s American ventures ended in economic disaster and resulted in disappointed and bitter investors, many of them widows and others of small means. Of course, it was during the 1930s that Avramenko did make what some felt were his greatest contributions to the Ukrainian cause: the production of two critically acclaimed Ukrainian-language films, Natalka Poltavka and Cossacks in Exile. However, while Martynowych acknowledges the importance of these achievements (and quite properly credits people like B-movie legend Edgar Ulmer who directed both of them), it is clear that Avramenko’s desire to create a “Ukrainian Hollywood” was always unrealistic and was more about Avramenko’s ego than “the cause.”

The remainder of this work is given over to a fairly sad rendition of what the author refers to as Avramenko’s “fugitive years” – hiding from creditors, currying favour with pan-Slavicists and the Russian emigre community, and being reduced to factory work to keep body and soul together. Almost amazingly Avramenko never saw himself as “yesterday’s man” and from the late 1940s until the 1970s he continued to try and build new communities of interest – in South America, Australia, England, Europe, and Israel – for his now hopelessly outdated take on Ukrainian dance and folk culture, always failing and always interspersed with trips back to Canada. This was the one place where he had not managed to burn all of his bridges because of broken promises and financial improprieties, the one place where he still had enough old friends and grateful students from the glory days of the 1920s; people that he could always count on for a de facto handout via a tribute banquet or a “Jubilee” honoring the old dance master.

At the end of the day, Martynowych has made an important, if all too brief, contribution to the literature on Ukrainian popular culture in North America. He has, of course, provided a much needed corrective to the extant historiography on Avramenko. I cannot help but liken his work to that of the Bollandists who examined the lives of the saints critically. Readers of Martynowych’s work will certainly understand that Avramenko was an important figure—indeed, one whose work and contribution are worthy of study and even commemoration, but certainly not sainthood. Even more to the point, however, is this: in the course of producing this fine little monograph on Avramenko, Martynowych has also provided readers with a brilliant little primer on Ukrainian diasporic politics, Ukrainian volunteerism in North America, the changing nature of the diasporic community over the years, and, perhaps most surprisingly, on North American popular culture during the 1920s and 1930s. Quite an achievement for 155 pages.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 25 July 2020