by Graham MacDonald

Parksville, British Columbia

|

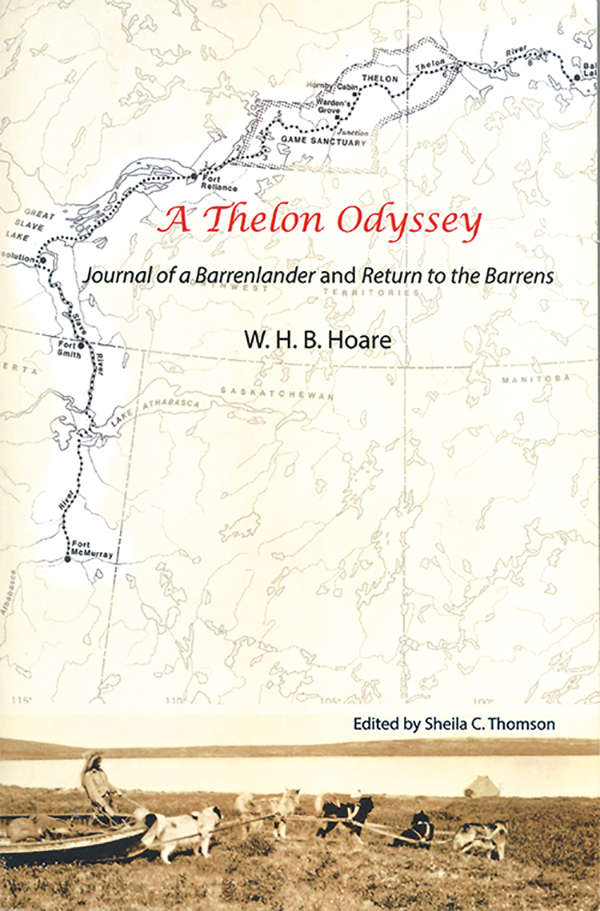

W. H. B. Hoare, A Thelon Odyssey: Journal of a Barrenlander and Return to the Barrens. Sheila C. Thomson (ed.). Ottawa: McGahern Stewart Publishing, 2014, 314 pages. ISBN 978-0-9868600-4-1, $24.95 (paperback)

The book under review is the outcome of a long Arctic apprenticeship by Ottawa-born William “Billy” H. B. Hoare (1890–1948). This is the fourth title released by McGahern Stewart Publishing in its enterprise of making available ‘Forgotten Northern Classics.’ Of the two works combined here, the first is a re-issue, available previously in a limited 1990 edition, also edited by Sheila Thomson (Hoare’s daughter). The second appears for the first time. Both concern the journals kept by Hoare when charged to explore and help organize the Department of Interior’s new Thelon Game Sanctuary, legally designated in 1927. This large and isolated tract of land lies between Great Slave Lake and Baker Lake in the old district of Keewatin.

The book under review is the outcome of a long Arctic apprenticeship by Ottawa-born William “Billy” H. B. Hoare (1890–1948). This is the fourth title released by McGahern Stewart Publishing in its enterprise of making available ‘Forgotten Northern Classics.’ Of the two works combined here, the first is a re-issue, available previously in a limited 1990 edition, also edited by Sheila Thomson (Hoare’s daughter). The second appears for the first time. Both concern the journals kept by Hoare when charged to explore and help organize the Department of Interior’s new Thelon Game Sanctuary, legally designated in 1927. This large and isolated tract of land lies between Great Slave Lake and Baker Lake in the old district of Keewatin.

Few Europeans had been in this area before 1900. Samuel Hearne skirted to the south of the sources of the Thelon River during his first trip inland from Churchill in 1770. George Back passed to the west in the mid-1830s while heading north. Sportsman Warburton Pike did not go farther east than Artillery Lake in the early 1890s. Geologist J. B. Tyrrell surveyed just south around Dubawnt Lake in 1896. His brother William provided the first useful maps of Thelon country in 1899, followed by those of David Hanbury in 1901. Not much more was added to local maps by the end of the First World War. What had been added in the north, however, was a certain institutional presence by the North West Mounted Police and various church bodies. The latter fact helps explain how Hoare eventually came to be involved in the Thelon project.

Hoare, a man of broad technical and classical education, had considered taking Anglican orders. His skills as a steam fitter and his spiritual outlook caused him to answer a call to serve as a lay Anglican Missionary in the high Arctic in 1914. His task was to transport a boat north from Fort McMurray for use on the Arctic coast in order to serve the ‘Copper Eskimos’ of the Coronation Gulf. Working between the Mackenzie Delta and Bathurst Inlet gave him a rare knowledge of the Inuit way of life and language. After marriage in Ottawa in 1919 he returned to the new community of Aklavik on the Mackenzie Delta, met Vilhjalmur Stefansson, and took an interest in the Government’s developing program to stimulate domestic caribou herding for the resident populations.

With his young family he returned to Ottawa in 1924 and joined O. S. Finnie’s Yukon and Northwest Territories Branch as a Special Investigator. Over the next three years he produced important reports on caribou habitat and movements over a large area east of Great Bear Lake. These were the credentials which led to an assignment, with Warden A. J. Knox of Wood Buffalo National Park, to organize the Thelon Game Sanctuary in 1928 and promote its importance to the local surrounding populations as a special area for caribou and muskox conservation. The immediate task was to establish the boundaries and put in place a central warden station.

Two geographical questions soon surface for today’s reader. The sanctuary was dominated by two rivers: the Thelon, rising in the southwest, and the Hanbury in the northwest. The warden cabin would be at the junction of the two, actually closer to the eastern boundary. Why haul tons of supplies all the way from Fort Reliance on Slave Lake via Pike’s Portage and Artillery Lake rather than from Baker Lake? The answer, in part, is that Hoare wanted a chance to see the western reaches of the sanctuary en route. This was reasonable perhaps, given accurate maps. The second question emerged from the slow realization that there was great cartographic confusion associated with the route from Campbell Lake to the upper reaches of the Hanbury River, supposedly accessible by a good channel. This was not so. In short, Hoare and Knox were soon asking a terrible question: where are we? The issue is well explained by K. L. Buchanan’s paper, helpfully included by editor Sheila Thomson as an appendix. Portages multiplied by the dozen for the two men in their search for the Hanbury. The resulting difficulties, their slow progress towards their destination, and the return to Fort Reliance by Christmas, 1928, are documented in agonizing detail. Wintering over at Reliance, the men then set out do it all over again, completing other outbuildings at ‘Warden Grove’ before Hoare came out to Baker Lake in August of 1929.

Hoare returned to Ottawa from Baker Lake in the fall of 1929 but was soon re-assigned to the Thelon. Return to the Barrens is the journal of this second trip in which he was charged with establishing warden facilities on the eastern boundary of the sanctuary where the Thelon River empties into Beverly Lake. Arriving via the Chesterfield Inlet route this time, the inland travels from Baker Lake were almost as gruelling as had been the first journey. Along the way, much is learned of the local Inuit people, assisted by good photos. Like the first assignment, it was understaffed and ad hoc in its provisioning and might as easily again have cost Hoare his life. Unforeseen contingencies were many, such as his abandonment on Schultz Lake in early September 1930, by his hired assistant. Carrying on alone he had to take shelter on what he called Prisoner’s Island at the west end of Aberdeen Lake. He was finally able to retreat back to Baker Lake with much loss of time. Wintering over there he prepared for overland treks of supplies to his destination in the spring and summer of 1931. The journal of this ‘Jack-of-all-trades,’ including lumberjack, ends with a final entry for July 31. Much had been accomplished to supply the new post, but with the onset of the Depression and a new government in Ottawa, O. S. Finnie’s Yukon and Northwest Territories Branch was eliminated and the staff rewarded with pink slips. A. J. Knox, after service at Thelon, lived for the rest of his life at Snowdrift, Great Slave Lake, dying at age ninety in 1976.

There is a David Thompson-like quality to Hoare’s journal entries: regular, disciplined, precise in the recording of useful geographical, wildlife or climatological data, and generally free of personal emotion or complaint in the face of adversity. It was a journal kept with a view to later reports. Happily, Hoare was hired on contract by C. H. D. Clarke when the latter was preparing his biological investigations of the sanctuary in 1937. Not so happily, Hoare died in an auto accident in 1948. With him went a great unwritten autobiography, but these journals provide remarkable insight into some of the memories it would have been based upon. Any wilderness parties going into Thelon country will want to have this volume included in the supplies.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 2 April 2020