by Robert H. Cockburn

The University of New Brunswick, Fredericton

|

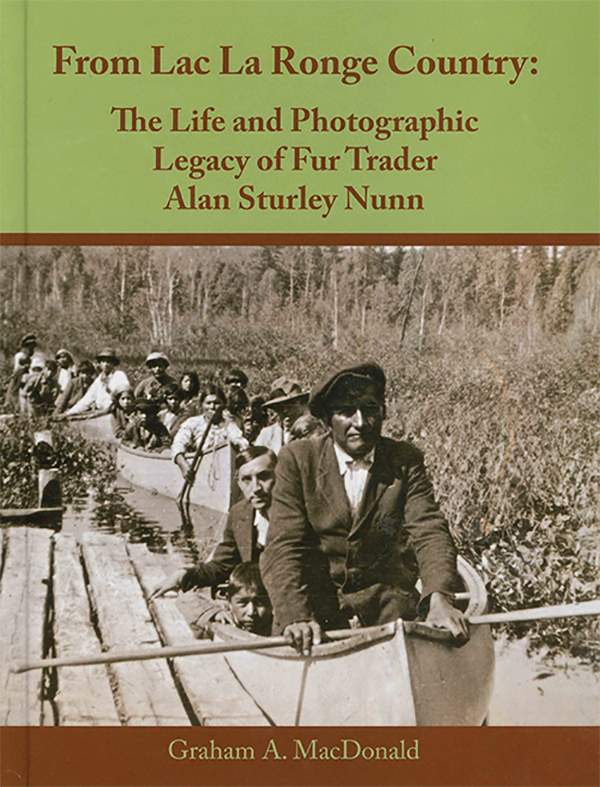

Graham A. MacDonald, From Lac La Ronge Country: The Life and Photographic Legacy of Fur Trader Alan Sturley Nunn. Fairmont Hot Springs, BC: MacDonald & Nunn Publishing, 2014, 134 pages. ISBN 978-0-9919178-1-5, $29.95 (hardcover)

The fur trade seems far distant now, an enterprise and a way of life gone these many decades, known to Canadians only from books, a few preserved historic sites, certain iconic paint-ings, and, every so often, a retrospective article in a magazine. Its legacy is mixed. One’s imagination may be stirred by the trade’s heroic age—the big canoes, the voyageurs and their songs, York boats, dog-teams in the snow, those immense distances yet to be disturbed by roads, telegraph, radio, or float planes. Yet such images mislead, for they have little or nothing to say about bitter rivalries, economic vicissitudes, cross-cultural tensions, or the despairs of solitary men, deep in the wilderness, suffering from illness, their own shortcomings, or crushing loneliness. Nevertheless, that pre-1900 northern world continues to exert its allure. By comparison, the fur trade in the first half of the twentieth century, its final era, has seldom attracted the public’s attention, other than when figuring in adventurers’ accounts of far northern travel. This period has, however, drawn the scrutiny of academics, whose predilections, and research, during the past fifty years have led them to call into question the motives, conduct, and attitudes of those who served the Hudson’s Bay Company and its competitors from 1670 to the Second World War. Their scholarly animus has been directed particularly at what they argue was the exploitation of native peoples, an exercise of power fostered not simply by avarice but also by the conviction of racial, cultural, and moral superiority.

The fur trade seems far distant now, an enterprise and a way of life gone these many decades, known to Canadians only from books, a few preserved historic sites, certain iconic paint-ings, and, every so often, a retrospective article in a magazine. Its legacy is mixed. One’s imagination may be stirred by the trade’s heroic age—the big canoes, the voyageurs and their songs, York boats, dog-teams in the snow, those immense distances yet to be disturbed by roads, telegraph, radio, or float planes. Yet such images mislead, for they have little or nothing to say about bitter rivalries, economic vicissitudes, cross-cultural tensions, or the despairs of solitary men, deep in the wilderness, suffering from illness, their own shortcomings, or crushing loneliness. Nevertheless, that pre-1900 northern world continues to exert its allure. By comparison, the fur trade in the first half of the twentieth century, its final era, has seldom attracted the public’s attention, other than when figuring in adventurers’ accounts of far northern travel. This period has, however, drawn the scrutiny of academics, whose predilections, and research, during the past fifty years have led them to call into question the motives, conduct, and attitudes of those who served the Hudson’s Bay Company and its competitors from 1670 to the Second World War. Their scholarly animus has been directed particularly at what they argue was the exploitation of native peoples, an exercise of power fostered not simply by avarice but also by the conviction of racial, cultural, and moral superiority.

One might well ask, then, if the story of an obscure man who served in the fur trade from 1905 to 1936 is worth the telling, and whether such a story can possibly be absorbing, let alone historically illuminating. From Lac La Ronge Country satisfies all three questions, thanks to the erudition, comprehensive research, and fluent style of its author, Graham A. MacDonald. But despite its title, this book is by no means exclusively a narrative of Alan Nunn’s fur-trading experiences, for MacDonald’s purpose has been to examine Nunn’s life in full, from birth to death. As he explains, although Nunn (1874-1946) kept a fur-trade diary between 1924 and 1936 while in the employ of Revillon Frères Ltd, it was “very much a work-a-day kind of business document: only occasional glimpses of his personal life are to be found there.” This diary, held by the Nunn family and shown to MacDonald, who has published frequently on northern subjects and whose knowledge of the fur trade is profound, spurred his interest in Nunn, but only, one suspects, because it had as company an album of evocative photographs, many of them striking, illustrating Nunn’s active career. Those images, once supplemented by family members’ recollections, genealogical records, and preserved correspondence, stimulated MacDonald’s inquisitiveness, giving the book substance and rewarding his reader with insights germane to particular cultural, religious, economic, and political connections that existed between Great Britain and the Dominion from the Victorian age into the early twentieth century.

Nunn, we learn, was born in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, into a prosperous farming family, was educated at Great Yarmouth Grammar School, and thereafter “mastered much of practical farm experience.” Then, in 1903, for reasons unknown, at age twenty-nine, Nunn left England for Saskatchewan: “With the turn of the century ... the Empire’s far reaches were again front and centre. There was no shortage of places on the red imperial map capable of drawing the attention of the restless or dissatisfied. Farmers, soldiers, prospectors, mechanics and workers alike were being encouraged to seek their fortunes abroad.” After working briefly on a farm, then as a hotel clerk in Prince Albert, in 1905 Nunn enlisted in Winnipeg with the Hudson’s Bay Company, serving with it until 1924, except during a brief, unsuccessful interlude as a free trader. “[He] became savvy in the routines of the Hudson’s Bay Company and of the ways of a so-called ‘tripper’ in the trade. Although a newcomer, he was a quick study and ... learned through his willingness to serve in isolated parts of northern Saskatchewan and Manitoba,” i.e., Lac du Brochet, South Indian Lake and other Nelson River District locales, Montreal Lake, and La Ronge. While at Brochet he dealt with the Woodland Cree and the Idthen-eldeli, the Barren Land Chipewyans; elsewhere he sought furs primarily from the Cree. His occupation was one demanding an affinity with the native peoples, shrewdness tempered by honesty, travelling skills of a high order in both summer and winter, and physical and emotional stamina.

In 1924, now age fifty, fed up with remote postings and disgruntled by his financial prospects with the Hudson’s Bay Company, Nunn joined their major competitor, Revillon Frères, who had begun operating in Canada in 1901; they welcomed his experience and competence. He was to serve them as their manager at La Ronge until 1936. In what constitute the most compelling chapters of this book, MacDonald astutely reviews the “French Company’s” history, its policies and field operations in the Churchill River country during Nunn’s tenure, and the challenges it encountered during this period: the vagaries of fur fashions, trade goods calculations, wilderness transportation, game laws, and, above all, coping with the competition of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the consequences of the fur crash of 1921, and the Wall Street disaster of 1929. These years also saw the gradual arrival of outboard motors and the bush plane, motorized freight ‘swings’, the radio, and the telephone. The old, tradition-bound North of Nunn’s earlier career was on its last legs, as was Revillon’s Canadian experiment. Unbeknownst to the traders and even the district managers of both organizations, the Hudson’s Bay Company had bought a controlling interest in Revillon in 1926 and had been secretly operating it as a form of subsidized competition after that. Revillon’s capitulation and the dire economic climate of the Great Depression led to the French Company being wholly absorbed by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1936, and with that, Alan Nunn retired.

To consider the full significance of the book’s title, attention now turns to Nunn’s two marriages and how the characters and callings of these women inspired the author to examine interwoven religious and educational characteristics of life in Lac La Ronge country. Nunn’s first wife, Esther Gilmour, after graduating from the Deaconess and Missionary Training House in Toronto, came out to work with the Rev. Albert Fraser at Christ Church Mission, The Pas. Her philanthropic idealism is associated, not without irony, with the historical impulse to convert native people to Christianity and, eventually, to educate them—an undertaking that acquired momentum from the evangelical fervour of nineteenth-century England. Like many such well intended, and self-serving, enthusiasms, this determination to ‘better’ the souls and minds of the Indigenous peoples was brought under political control, and by 1890 the Canadian government had decreed “a lack of choice on the part of those legally defined as Indians as to how their children were to be educated.” Nowadays, knowing its worst consequences, we deplore that edict. No such animadversion can have occurred to the dedicated Miss Gilmour when in 1922 she moved on to teach in All Saints Missionary School, in La Ronge, where she and Nunn married in 1926 and where she died in 1927 after giving birth to their daughter. Nunn soon remarried, to Barbara Allcock, a young woman from Nottinghamshire whose altruism resembled Esther’s. They met at the isolated post of Stanley Mission, where she was teaching Cree children. The couple found contentment, Nunn engaged anew with his demanding managerial routine, and she soon delighting in their son and taking enthusiastically to canoe travel, snowshoeing, and trips by dog team with her husband. With Revillon Frère’s demise in 1936, the Nunns relocated to Spruce Home, north of Prince Albert, where they ran a general store until Alan died in 1946, a long way from Bury St. Edmunds and a Suffolk farm. Barbara, who had left Sherwood Forest for the boreal forest, lived until 1977. It is fitting that Nunn Lake and Nunn River can be found on maps of Saskatchewan.

The written contents of From Lac La Ronge Country are complemented by the book’s physical and visual excellence. Lori Nunn’s design and layout are those of a first-rate talent. The evocative cover image, facsimile endpapers from Nunn’s diary, the clarity of the photographs, the binding, the quality of the paper used—all set a standard most publishers can only envy. The majority of the photographs were selected from the Nunn Family Collection; other photos and illustrations come from diverse sources. Coloured archival maps are strikingly reproduced. An Epilogue, nine pages of endnotes, a substantial bibliography, and an index reinforce the merit of this handsome, absorbing book. [1]

1. This reviewer has but two complaints, both minor: he regrets the written and pictorial attention paid the mountebank “Grey Owl,” and notices that two sources to which the reader is directed on page 112 in the endnotes fail to appear in the bibliography.

We thank Clara Bachmann for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

We thank S. Goldsborough for assistance in preparing the online version of this article.

Page revised: 2 April 2020