by Shirlee Anne Smith

Former Keeper, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives

|

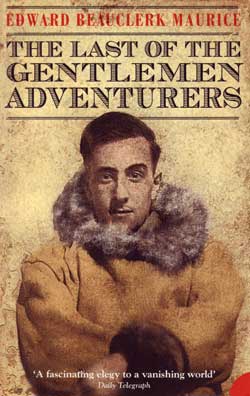

Born in 1913 in Somerset, England, Edward Beauclerk Maurice, like thousands of men before him, joined the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1930. Owing to the great economic crash of 1929 it was not a propitious year. It was difficult to find employment so he signed an agreement to serve as an Apprentice Clerk for five years. He was posted to Pangnirtung, Baffin Island. Here the Company traded goods for walrus oil, sealskins, and white fox furs. He waited more than half a century to tell his story. This book is an interesting account of a way of life that has vanished. It is the story of one man and his interaction with the Inuit while serving at only two posts: Pangnirtung and Frobisher Bay.

The HBC established a post at Pangnirtung in 1921 and Maurice’s description of the dwelling house would not have been a feature in Good Housekeeping. He moved quickly from his Victorian ideas of immorality to accepting the fact that the post manager had an Inuit common-law wife, by whom he had two children. This, of course, was quite acceptable to the Inuit. One of the most important nights of the week was Saturday when the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation relayed messages from friends and relations to the men and women of the Arctic. To his great surprise Maurice received a message from his mother who was then living in New Zealand. Except for the annual supply ship this was the only communication the fur traders had with the outside world.

There is an immediacy about the various encounters with Arctic life that offers a freshness and a feeling of witnessing what is being told. The detail is remarkable, and one wonders if the author did not keep a diary. When telling how the Inuit built their snowhouses he writes: “The snow must be carefully selected, firm but not brittle and all, if possible, from a drift formed by a single storm, as a block made up of layers from different drifts fractures easily at the joints.” A description of the actual construction follows.

High drama abounds in the book as the author recalls his deer hunting and whale hunting sojourns. His ministrations to the Inuit were constrained. In cases of illness his supply of medicines consisted of emetics and aspirins. There are some light moments as he organizes a type of field day with egg and spoon, sack, and kayak races to help the people forget their difficult winter months of darkness and sickness.

The Inuit are inveterate story tellers and the long days of darkness were spent retelling their legends. When asked to tell stories the author entertained them with one based on “The Walrus and the Carpenter.” It unfolded with the walrus and a carving man going to sea in a funny boat where they had a curious conversation with a passing seal. As their legends frequently have animals and humans conversing the tale was listened to with great attention. The women were entranced with the fairy tale of Snow White.

Edward Beauclerk Maurice (right) passes the reins of HBC post management to P. Dalrymple at Southampton Island, 1940.

Source: Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, 1987-205-591.

What this book lacked was a more knowledgeable editor, so that the factual errors, including the Company name being “The Gentlemen Adventurers Trading into Hudson’s Bay” could have been corrected. The formal name of the Company is The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson’s Bay. The Adventurers were “Lords and Proprietors”, but no where in the Charter does it state that they had to be Gentlemen. One also wonders about the use of the word “Last” in the title, especially when such arctic veterans as L. A. Learmonth, Chesley Russell, and Peter A. C. Nichols come to mind. It was somewhat surprising to have the author state as gospel the fable about the Indian, who wanted a musket from a trader, having to pile beaver skins one upon the other until the stack equalled the height of the gun. This popular fable was fully deconstructed in The Beaver magazine for September 1948, p. 46. Surely one of the strangest lines in the book is where the author states that at Pangnirtung in the springtime a southerly gale would bring “a whiff of spruce and pine.” This has been refuted by a person who lived in Southern Baffin Island for a number of years. An introduction, an index, and illustrations would have added immeasurably to the book. There is a good selection of photographs for the period in the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, such as those of Alan Scott, an Apprentice Clerk at Pangnirtung when Maurice arrived and manager from 1933 to 1935. Scott and his wife later made history of a kind by having the first non-Inuit child born at Arctic Bay, Baffin Island.

There are so many questions that will now never be answered, as the author died in 2003 at age 90 years. One wishes that he had been more forthcoming about the life of the settlement. What he thought of the three men from The Royal Canadian Mounted Police detachment, the missionaries, the staff at St Luke’s Hospital, is not known. Why, for instance, did he only write about Pangnirtung and Frobisher Bay, with no mention of Southampton Island and Sugluk where he also served? One can offer a number of reasonable guesses including that those first or six years of his service were the most exciting and deeply embedded in his memory. He left the Company in 1940, and joined the New Zealand Navy - never to return to the Canadian Arctic.

There are still many people living who served in the Arctic following Maurice’s service. They may be apt to give one long yawn and to say: “So What, We All Did Those Things.” But he left an intimate record of what life was like in the 1930s. It is hoped that the descendants of the people who lived at Pangnirtung and Frobisher Bay, especially those of Kilabuk and Bevee, Company employees at Pangnirtung, will read about this man who lived among them, learned their language, and cared about their welfare.

Page revised: 16 June 2012