|

Since the dismantling of European empires in the decades that followed the Second World War “imperialism” has most often carried negative connotations. Due to the recent conflicts in the Middle East, many in Canada and the West have once again taken “western imperialism” to task. Oftentimes, Canadian college or university students are some of the most vocal and passionate anti-imperialists. Yet that has not always been the case, as this study of student attitudes to imperialism indicates.

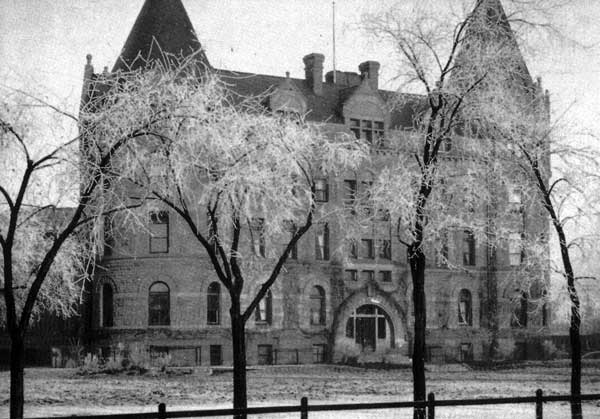

The students that this article focuses on were from Wesley College in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. [1] In 1877 Methodists received a charter for a college in the recently federated University of Manitoba located in Winnipeg. However, due to the need for planning, support and finances, classes in the arts and theology only began in 1888. In 1895 the large stone building that still survives was completed near Manitoba College (a Presbyterian college, founded in 1871). [2] In 1938, these two schools merged to become United College, and in 1967 continued as a part of the new University of Winnipeg. Wesley College saw itself as having a critical role to play in the development of the church and nation, for as Neil Semple notes:

The faculty and students saw themselves as the legitimate voice of the northwest. Wesley College reinforced this view by giving priority to training men and women who could fulfill the essentially missionary nature of much of the church’s work in the region and assumed a leading role in dealing with the challenges created by the arrival of vast numbers of non-English-speaking immigrants. It helped assimilate these new Canadians into the dominant Protestant culture of the nation. [3]

In the closing years of the nineteenth century the college had an approximate enrolment of 130 students, and enrolment increased almost every year. [4] While not without some tensions within the denomination, Wesley College (like other Methodist schools in Canada) admitted women on an equal basis as men. [5]

The focus of this study is on the attitudes of Wesley College students to the British Empire and Canada’s place within it during the years 1897-1902. The source for uncovering these attitudes is the student newspaper; the Vox Wesleyana. [6] This monthly publication began in 1897 under the leadership of Professor Riddell, and was published by students and for students of Wesley College during the academic year. [7] Its staff was comprised of seven or eight students, along with a faculty member. Like most student newspapers, the Vox had editorials on issues of the day, articles from students and faculty, articles from outside contributors, commentary on the college’s sports teams and how they were fairing against their competition, details of society meetings and events, and a section entitled “Local and Personal” that included gossip and personal anecdotes from campus. Within its pages, one also finds a great deal of religious commentary and religious news (e.g., news related to missions, YMCA reports, special church services).

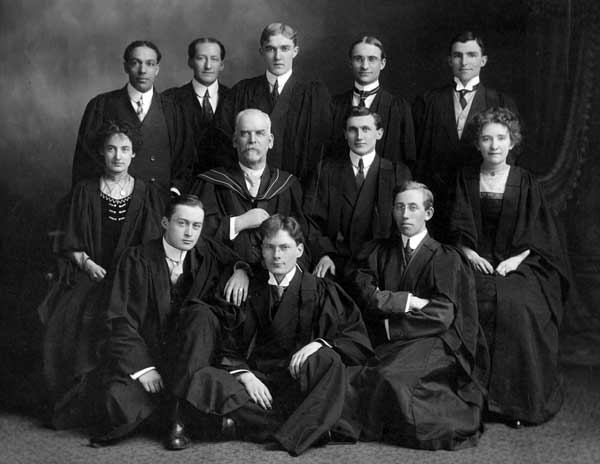

The Editorial Board of the Vox Wesleyana at Wesley College, 1910-11.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

Before looking at the actual contents of the Vox a few comments about the potential and pitfalls of using the paper as a primary source are necessary. Glenn Wilkinson has noted that the late Victorian newspapers are an “excellent source” of information for cultural and social historians. Because a newspaper needs to connect immediately with its readership there is a “form of two-way communication” between the paper and its readers, reflecting in its pages the immediate events and perceptions of the period. [8] That is certainly the case with the Vox. Without even necessarily trying to make it so, what the editors of the Vox included (or commented on) in the pages of the Vox when they reported on the life of the college is a helpful guide to the events and passions of late nineteenth century student life at Wesley College.

Of course, there are also pitfalls to using newspapers as primary sources. Peter Hennessy has noted that one of the most significant issues related to the use of newspapers as primary sources is editorial bias. He writes that the “value of any report or piece of commentary has to be judged in the light of a paper’s editorial predilections as well as the writer’s own bias. The fair-mindedness which ought to characterize the historian’s work cannot be assumed to govern that of journalists.” [9] Each year in the Vox there was a picture of the student editorial board and Professor Riddell (who often sat right in the middle of the group). What kind of influence did he (or the faculty as a whole) have on the student editors? Even without the question of Professor Riddell’s influence on the editors, the question remains as to the various opinions of the student editors themselves. How did their personal opinions influence the selection of material for the pages of the Vox, and how did their personal bias influence their interpretation of events that were reported on? The assumption under girding this research on the Vox is that both the potential and pitfalls of using newspapers as primary sources must be kept in mind. The pages of the Vox reveal much (but not all) about the life of students at Wesley College, but any such information gained must always be recognized as mediated through an editorial board that may or may not have been unbiased in the way it went about fulfilling its editorial duties.

The references to “empire” in the pages of the Vox during 1897-1902 indicate significant support among students of Wesley College for imperialism in general, and the British Empire in particular. In The Sense of Power, [10] the most important work on Canadian imperialism, Carl Berger explores the imperial attitudes among key leaders in Canadian society. The imperial attitudes of students in various colleges, however, have been for the most part ignored in his and in other works. One exception to this pattern is a relatively recent article by Sean Mills. Mills notes that imperial attitudes of Anglican students and faculty at Montreal Diocesan Theological College were quite high, and he argues that understanding this imperial sentiment is critical to a proper conception of how the school understood its mission in Canada and the world. [11] Due to the lack of previous research in this area, then, this discovery of imperial sentiment in Wesley College students will contribute to an understanding of how deeply rooted imperial sentiment was among college students. It was not just key leaders or clergy in loyalist Ontario who were enamoured with the British Empire; Methodist students at Wesley College in sparsely settled Western Canada were also ardent imperialists. This paper will also show how the imperial sentiment at Wesley College compels one to adjust contemporary conceptions of late nineteenth-century Methodist pacifism, Canadian imperialism, the goal of the nation-building churches, and the social gospel impulse within Methodism.

The latter part of the nineteenth century, up to the First World War, has been coined the “Age of Imperialism” [12] or the period of the “New Imperialism.” [13] Imperialism was a “movement sweeping Western Europe and North America” [14] during a period marked by the rapid expansion of already existing empires, such as Britain’s or France’s, or new ones such as Germany’s. The United States and Japan were also active in their quest for territory and empire. The country, which gained the most during this race for empire, was Britain. In various Canadian Methodist publications, this growth of the British Empire was looked upon with admiration, a great sense of accomplishment, and pride. The number of people within the empire was noted, with such details often being compared with the lesser growth of other European powers. [15] The Canadian Epworth Era’s brief comments provide a sense of this pride of empire. [16] It was noted that in 1800 the Empire had 115 million people, and in 1900 it had 390 million. Its geographical growth over the same period increased two acres per second. The empire was now ninety-seven times the size of the home country. Through other articles such as “More Empire Building” [17] the alleged benefits of the empire were proclaimed. Although Canada had celebrated its Dominion status in 1867 and was a young, optimistic nation, it remained a part of the British Empire. The empire controlled a vast number of territories, each of which had distinct relationships with the “mother” country. More “mature” territories, like Canada and Australia, had one type of relationship, whereas places such as Egypt or a newly invested territory in central Africa or the South Pacific had another. While French Canadians were relatively unenthusiastic about the British Empire, and saw the world and Canada’s place within it quite differently than English Canadians, [18] by the end of the nineteenth century [19] English Canadians took great pride in belonging to the largest empire that the world had ever seen. When Sir Wilfrid Laurier formed his government in 1896, imperialism “was fully in the saddle” in London. [20] Pierre Berton’s observation that the “youth of Canada breathed in the spirit of imperialism with their breakfast porridge” [21] aptly describes the depth of imperial sentiment in Canada at the end of the century. And as Page notes, no “single topic” moved “Canadians as powerfully and as emotionally as ‘The Empire.’” [22] Images and reminders of the empire were woven into the fabric of Canadian society; no school child in English Canada could avoid the flags, maps, songs, poems and lessons that spoke of the splendour and majesty of the British Empire and Queen, [23] nor any adult miss the imperial sentiment expressed in the press, novels, poetry, politics, and economics of the day. [24]

The events of the previous decade had engendered this growing passion for the empire. International tensions and uncertainty, tariff concerns with the United States (not to mention a fear of invasion by the U.S.), and the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 had all made closer ties with Britain seem not only natural, but also necessary. It was during the war in South Africa, however, that imperial sentiment was brought to its most excited, feverish pitch … As the Spanish-American War had aroused the United States so the South African War stirred Canadians … The Boer War was the great high-water mark of imperial zeal in Canada. [25]

Such excessive displays of imperial passion would not be seen again in Canada until the First World War. [26]

On 11 October 1899, Britain was officially at war in South Africa against the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State. [27] The war ended with a British victory in 1902. While the war was thousands of kilometres away from the shores of Canada, and Canada’s contribution of over 7,000 troops to the imperial cause was relatively small, the war is considered to be one of the critical events in the nation-building process of the young dominion. The development of Canada’s foreign policy and international reputation, the growth of Canadian nationalism, as well as the domestic divisions between French and English Canada, were all impacted by Canada’s participation in the South African War.

Like in every other Methodist publication across Canada, [28] there was no uncertainty expressed in the pages of the Vox that Canada was right to send troops to aid the empire in South Africa. When war broke out in South Africa, the Vox lamented the “war drum,” but made it clear that it supported Britain’s cause.

That dream of universal peace, when the war drum would throb no longer, seems not to find its fulfilment in the present … Thus for the second time in a few months we have seen the spectacle of a great nation forced to war in the cause of humanity. The United States freed Cuba from the tyranny of Catholic Spain, Great Britain goes to free her own people from a tyranny carried on in the name of religion, and to give her people that liberty which has been the proud possession of Britain’s for centuries. [29]

In the same issue the Vox published a poem entitled “Canada to England,” a poem that spoke of the bond between Canada and England.

Mother of many prosperous lands,

Thy children in this far off west,

Seeing that vague and undefined,

A cloud comes up to mar our rest,

Fearing that busy tongues, whose speech

Is mischief, may have caused a breach,

And frayed the delicate links which bind

Our people each to each,

With loving hearts and outstretched hand

Send greeting real and kind.

When recent danger threatened near,

We nerved our hearts to play our part;

Not making boast nor feeling fear;

But as the news of insult spread

We’re none to dally or to lag;

For all the grand old island spirit

Which Britain’s chivalrous sons inherit

Was roused, and as one heart, one head,

We rallied round our flag.

And now as then then unchaged (sic), the same

Though filling each our separate spheres:

Thy joys, thy griefs, and thy good name

Are ours, and or (sic?) in good or ill;

Our pride of race we have not lost,

And aye it is our loftiest boast

That we are Britons still!

And in the gradual lapse of years

We look that ‘neath those distant skies

Another England shall arise,

A noble scion of the old,

Still to herself and lineage true,

This is our hope, and as for you,

Be just as you are, generous, mother,

And let not those who rashly speak

Things that they know not, render weak.

The lies (sic?) that bind us to each other. [30]

The need to reassure England in light of “busy tongues” and “rash” words was most likely a reference to the domestic debate over whether or not to send Canadian troops to South Africa. [31] George Emery has noted how western Methodists often felt alienated from the more powerful and populated centers in central Canada. [32] One wonders what part the empire played in helping western Methodist students at Wesley College feel as though they were connected to something bigger than their sparsely populated often lonely part of the new nation, and even connected to something bigger than central Canada. The language of this poem expresses a loyalty that speaks of a very real sense of “oneness” with the “mother” country. The war may be thousands of kilometres away to the south, and England thousands of kilometres away to the east, but the passions in this poem express an intimacy with England and its empire that could not be broken by any distance.

There are other examples of support among the student body for the imperial adventure in South Africa. One example is an essay written by a student named Thomas D. Brown, [33] another is the response to a student’s enlistment in the Strathcona Horse. Brown’s prize-winning oration entitled “The South African War” must have been delivered (to whom is not stated) late in 1899 or very early in 1900, since the text of the speech was published in the January 1900 issue of the Vox. [34] Brown’s speech expressed many of the popular reasons why Protestant’s supported the war. He lamented the outbreak of war, and left the judgement of the causes to others. What he did argue, however, was that a British victory would ultimately bring about “great good.”

But taking matters as I find them, I propose to show in the short time left at my disposal that the cloud of devastation now bursting upon the Transvaal has yet a silver lining, and that over the area where desolation is now rampant great good will come as a result of this war.

The “great good” that Brown was referring to was the establishment of British supremacy in South Africa and the uniform system of government that would follow. Such rule, he believed, would end internal strife and bring justice to “every race and creed.” Another good from the war was the unification of the empire.

But in another way, and not less potent, the unity of the Empire will be promoted by this war. You remember the enthusiasm that spread all over our country when our boys left to aid the Empire’s cause in Africa. You remember, too, the thrill of joy and pride that swept across our land when, a few days ago, tidings came that our boys were going to the front to fight side by side with boys of old Britain. What did it mean? It meant that, though colonists in name, we had ceased to be so in fact, and had become citizens of that mighty Empire, whose dominion is worldwide and whose power is eternal.

A final benefit to a British victory would be the advancement of missions. The nineteenth century was marked by the rapid rise of English-speaking Protestant mission work, [35] and for decades the Boer treatment of the African indigenous peoples had been lamented by missionaries. [36] Brown was convinced that a British victory would put an end to such abuses. [37] The end result would be a furthering of mission work within the empire, the “mightiest of earthly agencies for the converting of the world.” Brown’s closing comments provided his listeners with a stirring post-war vision of Africa.

Thus Africa, from being a land of lions and jungles, the home of warring tribes and hostile races, known to the world as “The Dark Continent,” will become the home of peaceful and prosperous millions, will welcome to her shores the industrious from all lands, and, being united in her aims and aspirations, will, under the blessings of British institutions, take the place among the continents that belongs to her by the design of nature.

Such naïve optimism and idealism was not unique to the young student Brown, nor was the linking of imperialism and missions unique, for similar statements were made by men and women of all ages throughout the empire during the war.

Another example of student support for the empire is that of Alfred N. Daykin’s enlistment in Strathcona’s Horse. Due to the dismal performance of the British army in the early months of the war, there was a call for more mounted units to join the army already in South Africa. Daykin was a Wesley College student who volunteered for Strathcona’s Horse, which left Canada for South Africa in March 1900. Daykin’s decision to leave his studies to fight for the empire was not criticised by the Vox. On the contrary, Daykin’s actions made him a hero. [38]

Alfred N. Daykin, a Wesley College student, left Canada for South Africa in March of 1900. Daykin’s decision to leave his studies to fight for the empire against the Boers was not criticised by the Vox Wesleyana. According to the paper, a meeting at the college “concluded with cheers for Mr. Daykin, Lord Strathcona, and the Queen … “. This depiction of Daykin is from the Vox Wesleyana of October 1900 and shows him in the uniform of the Strathcona’s Horse.

Source: The United Church of Canada / Victoria University Archives

Before Daykin left Wesley College, a special assembly was called. Despite there being only a “few hours’ notice” before the meeting, the February 1900 issue of the Vox reported that the students turned out “in full force” and that a “large representation of friends from the city” “literally packed” the Assembly room. [39] Various professors, Principal J. W. Sparling, and many others, spoke to the assembly. In the opinion of the Vox, it was quite a successful event and one of the most significant in the life of Wesley College.

Without doubt this was one of the most interesting and memorable meetings ever held in Wesley College, and as the meeting concluded with cheers for Mr. Daykin, Lord Strathcona, and the Queen, the signing of “God be with you till we meet again,” we unconsciously joined hand and heart with those who at the seat of war are fighting for God and native land.

The following month the Vox published a brief biography of Daykin, along with some very brief information on his arrival in Ottawa. [40] In subsequent months, the Vox reported on the military exploits of Daykin. In October 1900, an extensive article on Daykin (along with a picture of Daykin in uniform) was published. [41] The article began with a brief explanation as to why Daykin enlisted in the army. It was said that had been caught up in the “flame of loyalty to motherland” during the early months of the war, and was “discontented to pour over books” when Britain experienced reverse after reverse in Africa. As a result, he “unflinchingly left his home and surroundings” to fight for “freedom, justice, Queen and Empire.” The remainder of the article brought the Vox readers up-to-date on his South African exploits. After a description of a few battles, the article pointed out that Daykin and a few of his comrades were taken prisoner in July 1900 by “overwhelming numbers of the foe.” Nothing was known of Daykin until two months later, when he and his fellow prisoners were released at Noortgidart on 9 September 1900. The article concluded with the statement, “we, his fellows of Wesley, are longing for the day when we can welcome back to College or (sic) patriotic, brave and illustrious comrade.”

A few more articles covering Daykin’s military career were printed. In December 1900 Daykin’s imprisonment was described, along with his experiences immediately following his release. [42] It appears that after his release Daykin became quite ill with enteric fever, and was confined to bed for six weeks. In January 1901 the Vox printed some of Daykin’s correspondence regarding his plans to return to Canada after his year of service had expired. [43] In March 1901 one last bit of correspondence from Daykin was printed. [44] This portion described how Daykin had plans to stay in England for a while and would not be able to get back to Wesley College before the semester was over. The Vox concluded the update by expressing disappointment that the “boys” would not be able to “give him a reception such as is his due.”

The examples of Brown and Daykin indicate that the notion that Canadian Methodists were pacifists in the years leading up to the First World War needs to be reconsidered. [45] Like other Methodist publications across Canada at the time, nothing in the pages of the Vox expressed opposition to the war. In fact, if the Vox indicates anything, it indicates that there was widespread support for the empire and war among students. This response by the students was in many ways precedent setting, for in the next war that Canada participated in (the First World War) students from Wesley College would also join to fight alongside of Britain and the empire. [46]

It seems quite clear that imperial sentiment spoken of by Berger and others, and reflected in other Western Methodist publications, [47] was deeply felt by the students at Wesley College. Unlike today, when imperialism is almost universally considered to be a bad thing, the students at Wesley College considered the British Empire to be God’s providentially established tool to spread Christianity and civilisation around the globe, and imperialism (in its ideal form) was something that actually aided other peoples and nations. Also, unlike today when the idea of Canada being a part of an empire seems foreign and unbecoming of an independent nation, the students at Wesley College could not conceive of a Canada outside of the empire. A closer look at a few examples in the Vox will illustrate these points.

In November 1899, the Vox printed the text of an address delivered in Aberdeen Scotland by Dr. Kilpatrick. [48] The article praised the reign of Queen Victoria and outlined the ways in which progress had marked “every department of human activity” during her reign. The first progress noted was that of the expansion of the empire. The supposed “haphazard” and unintentional growth of the empire was considered to be convincing proof of the Providential nature of the empire (in other words, the British had not tried to gain an empire, it had just “happened” to them). Such “evidence” of God’s providential work to raise up Britain also strengthened the conviction that God had a “special function” for the empire. Such an empire, it was argued, would continue to thrive as long as it stayed obedient to its mission.

The people of a small country like Holland, whose history is in a sense concluded, might be excused if they were to slacken their energies and lose a living interest in the world’s progress. Not so we. Our race ought to be continually revivified by the great task, which awaits it, and should be saved from the fate of becoming exhausted and effete. The doom of Babylon, of Tyre, of Carthage, need not be ours, if we are true to our imperial mission.

What exactly was its imperial mission? The empire was to seek to abolish poverty, end injustice, introduce good government and bring Christianity to all parts of the globe. As Kilpatrick stated:

It falls to us as the mightiest power in the world, to cast our weight into the scale of liberty for the oppressed, justice for the week, peace and well-being for all. Our progress designates us to this pre-eminent function of taking the widest interest in the races of men, and laboring for the moral elevation of mankind.

Kilpatrick was not alone when he linked the empire with mission, for this same sentiment was imbedded within other articles in the Vox. For instance, when the war was announced, it was declared that Britain would be fighting for “the cause of humanity,” [49] and one of the professor’s during Daykin’s send-off mentioned how Britain only went to war for principle and for right. [50] These comments from Kilpatrick (and others) are not a surprise, for as Berger notes, the imperialism of the day was infused with a sense of mission. [51] There was such a thing as false imperialism (the kind that exploited people and nations), but true imperialism was what the empire needed to strive towards. There was also a marked note of racial superiority in such comments. Again, this is no surprise, for as Miller notes, the imperial sentiment of the day was intimately associated with Social Darwinian theories of race. [52]

Wesley College has been identified as a “vigorous source” of the social gospel in Canada, [53] and as early as 1938, a jubilee history of Wesley College commented on how the school had been known as the “home of radicalism.” [54] In its most basic sense, the social gospel was concerned for the advancement of social justice. What this study also indicates is that the social gospel radiating out of Wesley College needs to be placed within a larger imperial framework. In the language used there was no substantial difference between Christianizing particular parts or peoples of the Canadian nation and Christianizing parts or peoples of Africa. The racial superiority so prevalent within such imperialism was also a component within the social gospel movement. Referring to this period being studied, Myra Rutherdale declares that it was “an age of classification” and that the “discourse of difference” was an everyday occurrence. [55] Terms like “race,” “breed,” “stock,” “native” and the like were quite common and, for most, were considered to be unoffensive. For instance, even such a socially progressive leader such a J. S. Woodsworth (one time a student at Wesley College – class of ‘96) used such racial categories. [56] Rutherdale’s work indicates that such terms were an everyday part of the Canadian missionary’s experience within the Canadian west. The point being made here is that it such categories were a part of the churches’ social reform language, as well as language of empire.

The abuses of the empire were lamented (and calls were made for citizens to see to it that these abuses ended). [57] However, the advantages of British rule were so closely identified with the ideals of the social gospel that any advance of the empire was, in a sense, a partial fulfillment of the social gospel dream. For instance, it was claimed that the war in South Africa was a war “in the cause of humanity” and would bring liberty to the area. [58] One article in the Vox associated the advancement of the empire in the Sudan with the promotion of literacy and education, and quoted a poem by Kipling to press home the point.

They do not consider the Meaning of Things;

they consult not creed nor clan.

Behold they clap the slave on the back and

behold he becometh a man!

They terribly carpet the earth with dead,

and before their cannon cool,

They walk unarmed by twos and threes to call

the living to school. [59]

Of course, such optimistic appraisals of the benefits of empire have had their critics. [60] There are also contemporary historians who claim that, out of all options available in the late nineteenth century, the British Empire was the best option at the time. [61] Whatever one thinks of the empire today, the point being made here is that the students of Wesley College believed that its rule brought a significant degree of stability, justice, and Christianity to its subjects. The importance of this link between the empire and justice should not be underestimated, for in both the South African War and the First World War social reformers were convinced that a victory for the empire on the battlefield would further their social reforms. [62]

Another example of imperial sentiment can be found by looking at the response to Queen Victoria’s death early in 1901. [63] On 22 January 1901, after a reign of nearly 64 years, and while Britain and its Empire was embroiled in its war in South Africa against the Boers, Queen Victoria died. The death of Queen sent shock waves around the empire and around the world. If one wonders how deep the imperial sentiment ran in the Canadian Protestant churches, the reaction to the Queen’s death should lay to rest any doubt that the Queen was also dearly loved by many of her Canadian subjects. In the first issue after her death, the Methodist flagship publication the Christian Guardian declared:

Our Queen is crowned in heaven. It is truest to think of her not as dead, but as alive in the land where no death comes. In her earthly life she was greatly honored and deeply loved – her sovereign position brought her unbounded honor, but her pure, wifely, womanly heart brought her boundless love. The honor fades, but the love remains, chastened in sorrow’s fires. England’s noblest Queen and greatest Soverign (sic), we love thee still. [64]

Wesley College, now a part of the University of Winnipeg, no date.

Source: University of Winnipeg Archives

The Guardian, however, was not alone in its sentiments, nor in its reporting on the events surrounding her death. In the weeks immediately following her death, the major (and most minor) religious publications all noted her passing. [65] Oftentimes Ontario is understood to be the province where imperial sentiment was the strongest. However, Protestant commentary on her death ranged from western to eastern Canada. [66] The Vox was no exception in this regard, and the students at Wesley College mourned the loss of their Queen. On 1 February 1901, the regular routine of student life was brought to a halt, and classes were cancelled for the day, so that everyone could attend a special memorial service. [67] Held in Convocation Hall at 11:00 am, the memorial service included special hymns, scripture readings, and addresses by various faculty. The singing of “God Save the King” was also sung for the first time.

The pages of the Vox included tributes to the Queen. The front cover of the January 1901 issue had a poem entitled “Victoria” printed on it. Like many other poems published at the time of Victoria’s death, [68] the poem painted a picture of the ideal queen whose death was universally mourned.

Over the wild Atlantic wafts a sound

Of sorrow, wrung from half a continent;

Mingling its sadness with the grief profound

That from Britannia’s woe-crushed heart finds vent.

Dead is the Queen, whose long and lustrous reign –

More than all others in its length of years –

Has won her glory, and, more precious gain,

Her people’s loyal love – and now their tears!

Vale (sic ?) Victoria; the Good, the Great!

Each nascent nation of the world-wide sphere

That owned thy sway, and mourns this stroke of Fate,

To deck thy tomb with emblem meet draws near.

Thy daughter of the North, disconsolate,

A wreath of maple lays upon thy bier. [69]

The editorial and articles in the same issue echoed these sentiments. Queen Victoria had been the ideal monarch, for she did not force compliance and loyalty. Unlike other leaders such as Alexander or Caesar who merely bowed people’s forms, Queen Victoria, it was argued, had led people to willingly bow their hearts and wills. [70] Her noble and virtuous character had shaped the character of Britain and its empire, and without her and her unceasing devotion to duty, self-sacrifice and justice, the greatness of the empire would have been of a “vastly lower type” and the condition of the world would have been even darker.

No other civilization was ever so tempted to fall down and worship Croesus, nor perhaps any so much disposed to do it. When, then, the first woman of the Empire and the occupant of its throne appears, who, though freed from almost every restraint which guards the private citizen against his weaknesses, follies and passions, who, though subjected to great and alluring temptations, has been constantly and manifestly animated by devotion to the right and good, and by an austere, laborious and intelligent discharge of official and private duty, who will say that such a character has not secured for the age and for the world results truly great? [71]

It was argued not only that the Queen’s character changed the world for good, but also that the Queen’s character cemented the bonds between Canadians and the Queen. Why were Canadians so loyal to a monarch so far away? As one editor notes, it was due to the bond created by the Queen.

A sovereign most have never seen, a home we have never entered, a life so remote from the lowly round of ours has yet so moved us. While we own with pride ourselves a part of her Empire, it is yet a “crowned republic,” and we are republicans by birth and native air. But the subtlety of this condition of thought in America to-day eludes analysis. We have of late years scarce been thinking of our Queen as mortal. Nevertheless, the “bond and symbol” of our Empire has passed away … None can say how [the Queen’s actions] vitalized and humanized the official bond. [72]

On the same pages as these glowing eulogies there was loyalty expressed to the new King and Queen, [73] and after the new King Edward VII’s son George, Duke of Cornwall and York, visited Canada later that year expressions of loyalty were still strong. [74]

Such support for the monarchy and empire among the students at Wesley College supports Berger’s and other’s conclusions that imperialism was a significant form of Canadian nationalism. Yet it also indicates that support for the empire within the churches went deeper than just key leaders, that passionate imperial sentiment extended beyond the borders of Ontario, and that imperial attitudes were to be found among Methodist students no less than among Anglican students. Any discussion of Canadian imperialism must include Methodist college students in the newly settled west.

These conclusions also force one to adjust the “churches as nation-builders” thesis. While the attitude of the churches towards Confederation was ambivalent, [75] by the turn of the century the Canadian Protestant churches had captured a vision for the new Dominion and had taken it upon themselves to be “nation-builders.” As Phyllis Airhart notes, this nation-building ethos was widespread among its leaders and far-reaching in its application. [76] One practical expression of the nation-building passion of the churches, not noted by Airhart, was the way in which the churches supported the nation and empire. Desmond Morton has noted how the war “fostered English Canadian nationalism.” [77] What is noteworthy is that Canada’s strong connection to Britain and empire was not seen by the students at Wesley to be incongruous with the rising patriotism. In fact, to be a patriotic Canadian was concomitant with loyalty to the Britain and the empire. In the pages of the Vox, it was impossible to envision a loyal Canadian as disloyal to the empire, for Canada’s future as a nation was intimately tied to that of the empire. While the “nation” that they were trying to build may not reflect contemporary images of what being “Canadian” means, it certainly was a popular one at the end of the nineteenth century. [78] That is not to say that there was always a clearly defined meaning as to what this imperial sentiment actually meant in regards to the daily relationship between Great Britain and the rest of the empire. Much of the support simply reflects a genuine desire to come to the aid of “mother” Britain in her time of need, such as that expressed in the poem “Canada to England.” [79]

It should also be noted that the Brown’s linking of missions with imperialism was not unique. The imperialism of the day tied missions to the fulfillment of God’s purpose for the young Dominion. Many saw Canada as having a uniquely religious duty on the continent and around the world. Not to live up to this responsibility was to forsake God’s calling. [80] While French Roman Catholics did not share in the distinctly Protestant interpretation of this mission, [81] many English Protestants understood missions to be an integral part of this providentially arranged calling. Sean Mills has shown how this fusion of mission responsibility and national destiny manifested itself in domestic Western Canadian mission work. [82] Berger has demonstrated that this national destiny was intimately connected with foreign mission work. In both cases, domestic and international, mission-work and the national purpose were inextricably bound together. Without the empire, this providential calling could not be fulfilled as effectively. Conversely, the spreading of the empire led to a furthering of mission work, as Brown noted in his prize-winning speech at Wesley College. [83]

In the final line of one of the poems published in the Vox there is an interesting typo. Speaking of the bond between Canada and England, the line should read “The ties that bind us to each other,” but was mistakenly printed “The lies that bind us to each other.” [84] The students of Wesley College were, no doubt, like many students today. They had dreams, ambition and a desire to make a difference in their nation and world. Also, (no doubt like many students today) the students of Wesley College believed in the dominant ideology of their day. In the case of Wesley College students, it was an ideology often riddled with assumptions about race and justice that today seem like more like lies rather than ties. But whatever one thinks of the empire today, the students then were firmly on the side of empire. Jonathan Vance’s study of the meaning of the First World War is helpful here. Vance concludes that the meaning found in the First World War in the decades that followed the First World War was not something that was “concocted by elites.”

Social control may have been a factor in the minds of some elites, but the memory of the war as a nation-building experience would not have caught on had it not been able to accommodate the widespread need to find meaning in the war. To dismiss the dominant memory as elite manipulation is to do a disservice to the uneducated veteran from northern Alberta who wistfully recalled the estaminets of France, the penurious spinster in Vancouver who sent a dollar to the war memorial fund, or the schoolgirl who marched proudly in a Nova Scotia Armistice Day parade. People like this embraced the myth, not because their social betters drilled it into their minds by sheer repetition, but because it answered a need, explained the past, or offered the promise of a better future. But they did more than simply embrace the myth: they helped to create it. By their very actions, each of these people played a role in nurturing the nation’s memory of the war and giving it life within their consciousness as Canadians. That memory was not conferred on them from above; it sprouted from the grief, the hope, and the search for meaning of a thousand Canadian communities. [85]

While Vance is referring to post-First World War memory or myth, his point is equally applicable to the situation of the students at Wesley College. Imperialism coloured their understanding of justice, shaped their views of race, informed the type of nation being built, influenced the role and location of missions, and provided a sense of identity and meaning in a world filled with uncertainty and conflict. Indeed, to understand the students of Wesley College we must see them as young idealistic students in the newly-born nation of Canada, but also see them as they saw themselves: “citizens of the mighty Empire.”

1. For a detailed history of the college, see Watson Kirkconnell, The Golden Jubilee of Wesley College, Winnipeg, 1888-1938 (Winnipeg: Columbia Press, 1938); Arthur Stewart, A History of Wesley College, Winnipeg (Winnipeg, 1938); Alfred G. Bedford, The University of Winnipeg: a History of the Founding Colleges (Toronto/Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1976). For a discussion of the school in the larger context of denominational history, see George Emery, The Methodist Church on the Prairies, 1896-1914 (Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001); J. H. Riddell, Methodism in the Middle West (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1946), 186-190; Neil Semple, The Lord’s Dominion: The History of Canadian Methodism (Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996), 252-253.

2. The four colleges founded in Manitoba in the nineteenth century were St. Boniface College - Roman Catholic (1819), St. John’s College, known as the Red River Academy until 1850 - Anglican (1821), Manitoba College - Presbyterian (1871) and Wesley College (1888).

3. Semple, The Lord’s Dominion, 253.

4. For a more detailed summary of enrolment statistics, see Cummings, A History of Wesley College, appendix.

5. Semple, The Lord’s Dominion, 253.

6. The Vox Wesleyana can be found at the United Church archives at Victoria University at the University of Toronto.

7. Bedford, The University of Winnipeg, 37-38.

8. “¼ images in newspapers had to conform to the perception of war that readers already held. In this regard, newspapers had little of no thought for posterity or future reputations of their creators, and they needed to create and foster an immediate connection with their reader audiences. This makes the newspapers a form of two-way communication, with readers more than ‘blank slates’ awaiting to be etched with how to think about the world by the press.” See Glenn R. Wilkinson, “‘To the Front’: British Newspaper Advertising and the Boer War,” in The Boer War: Direction, Experience and Image, ed. John Gooch (London: Frank Cass, 2000), 203-204.

9. Peter Hennessy, “The Press and Broadcasting,” in Contemporary History: Practice and Method, ed. Anthony Seldon (Basil: Blackwell, 1988), 20. Christopher P. Campbell has shown how contemporary news media is not unbiased in its reporting. The late Victorian period was no less a time (most likely more) when categories of “race” played an important part of public discourse. That being the case, it should come as no surprise to find that within the Vox racial biases are expressed. Nevertheless, those attitudes in and of themselves reveal something about the students and imperialism. See Christopher P. Campbell, Race, Myth and the News (London: Sage Publications, 1995).

10. Carl Berger, The Sense of Power: Studies in the Ideals of Canadian Imperialism, 1867-1914 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1970).

11. “‘Preach the World:’ Canadian Imperialism and Missionary Outreach at the Montreal Diocesan Theological College, 1892-1903,” Journal of the Canadian Church Historical Society 43 (2001): 5-38.

12. Heinz Gollwitzer, Europe in the Age of Imperialism, 1880-1914 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1969).

13. Harrison M. Wright, ed., “The ‘New Imperialism,’ Analysis of Late Nineteenth-Century Expansion,” (Lexington, Massachusetts: D. C. Heath and Company, 1961).

14. Robert Page, The Boer War and Canadian Imperialism (Ottawa: The Canadian Historical Association, 1987), 7.

15. “Facts about the British Empire,” Onward, 30 June 1900, 206; “The Growing Tongue,” Canadian Epworth Era, April 1901, 99; Onward, 8 June 1901, 184; “Wondrous Developments of the British Empire,” Onward, 25 August 1900, 269.

16. “Growth of the British Empire,” Canadian Epworth Era, December 1900, 355.

17. “More Empire Building,” Methodist Magazine and Review, September 1901, 270-271; “More Empire Building,” Onward, 12 April 1902, 115.

18. Stacey argues that the French willingness to fight for the Pope in 1868 illustrates how differently Quebecers saw the world. See C. P. Stacey, Canada and the Age of Conflict, vol. 1 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984), 7. Silver claims that there was a French Canadian imperialism, except that this imperialism saw its divine mission to be the preservation and promotion of Catholicism in North America and the world. In other words, it took on the role of France as the protector of Catholicism. See A. I. Silver, “Some Quebec Attitudes in an Age of Imperialism and Ideological Conflict,” Canadian Historical Review 57 (December 1976): 440-460.

19. Page and Stacey assert that in the years immediately following Confederation, English Canadians were loyal to Britain, but not at all excited about imperial ventures, and imperialism in general. See Page, The Boer War and Canadian Imperialism, 3; Stacey, Canada and the Age of Conflict, 40-44.

20. Stacey, Canada and the Age of Conflict, 52.

21. Pierre Berton, Marching As to War: Canada’s Turbulent Years, 1899-1953 (Canada: Anchor, 2001), 24.

22. Page, “Canada and the Imperial Idea in the Boer War Years,” Journal of Canadian Studies (February 1970): 33.

23. See Berton, Marching As to War, 24; Daniel Francis, National Dreams: Myth, Memory and Canadian History (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1997), 52.

24. “It [Imperialism] exhibited its most intense form in the popular press, but also found expression in the novels, poetry, economics, philosophy, and sermons of the era.” See Page, Imperialism and Canada, 1895-1903 (Toronto: Holt, Rinehart and Winston of Canada Limited, 1972), 2. See also Page, “Canada and the Imperial Idea in the Boer War Years,” 33-49.

25. Page, Imperialism and Canada, 1895-1903, 5, 12.

27. This war in 1899 - 1902, called the South African War, was the largest war that Britain fought between the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War. It is often more commonly known as the Boer War.

28. For a detailed analysis of the response of the Canadian Protestant Churches to the war, see Gordon L. Heath, “The War with a Silver Lining: Canadian Protestant Churches and the South African War, 1899-1902 (unpublished dissertation, Toronto: University of St. Michael’s College, 2004).

29. “Our War,” Vox Wesleyana, October 1899, 2-3.

30. Anonymous, “Canada to England,” Vox Wesleyana, October 1899, 5-6.

31. For a helpful summary of the events surrounding the pressure placed on Prime Minister Laurier, as well as his initial refusal to commit to sending troops, see C. P. Stacey, Canada and the Age of Conflict: Volume 1: 1867-1921 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984), 52-84.

32. Emery, The Methodist Church on the Prairies, 20-29.

33. For biographical information on Brown, see Vox Wesleyana, Summer 1900, 135-136.

34. Thomas D. Brown, “The South African War,” Vox Wesleyana, January 1900, 59-61.

35. The nineteenth century has been coined the “great century of Protestant missions.” See Kenneth Scott Latourette, The Great Century, A.D. 1800 - A.D.1914 (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishing, 1941), 1. British Protestant denominations were at the vanguard of this missionary movement, sending 9,014 missionaries out of a total of 17,254 Protestant missionaries from all countries. The next closest Protestant missionary-sending nation was the United States. Out of those 17,245 Protestant missionaries, the U.S. sent 4,159. See Brian Stanley, The Bible and the Flag: Protestant Missions and British Imperialism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Leicester: Apollos, 1990), 83. In fact, “by the middle of the nineteenth century, the ‘missionary spirit’ was being hailed by contemporaries … as the ‘characteristic feature’ of the religious piety for which the Victorians were rightly renowned.” See Susan Thorne, Congregational Missions and the Making of an Imperial Culture in Nineteenth-Century England (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 5.

36. See Stephen Neill, A History of Christian Missions (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1986), 264. See also James Greenlee and Charles Johnston, Good Citizens: British Missionaries and Imperial States, 1870-1918 (Montreal/Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999).

37. Brian Stanley has noted how many Protestant British missionaries often saw the Empire as a solution to missionary woes. See Stanley, The Bible and the Flag.

38. The Vox was not the only church college student newspaper to praise the students or alumni who joined in the imperial cause. For example, see Trinity University Review, November 1899, 101; “Trinity Men in South Africa,” Trinity University Review, February 1900, 21.

39. Vox Wesleyana, February 1900, 73.

40. “Local and Personal,” Vox Wesleyana, March 1900, 105-106.

41. J. L. Veale, “Our Scout in the Transvaal – A.N. Daykin,” Vox Wesleyana, October 1900, 3-5.

42. “Our Scout in the Transvaal,” Vox Wesleyana, December 1900, 47.

43. Vox Wesleyana, January 1901, 81.

44. Vox Wesleyana, March 1901, 114.

45. John W. Grant, The Church in the Canadian Era (McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited, 1972, reprint edition Vancouver: Regent College Publishing, 1988), 114.

46. See Bedford, The University of Winnipeg, 123. This pattern can also be seen in certain Anglican colleges. For example, see T. A. Reed, ed., A History of the University of Trinity College, Toronto, 1852-1952 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1952), 236-238, 247; L. S. Loomer, King’s-Edgehill School, 1788-1988 (Windsor: King’s-Edgehill School, 1988), 34-36.

47. Two western-published Methodist publications, the Indian Advocate and the Western Methodist Recorder, and the Ontario-published (but circulated in the prairies as the official Methodist western publication) Christian Guardian, contained significant examples of support for the British Empire and Canada’s role in it. See Heath, “The War With a Silver Lining.” Of course, the fact that the Ontario-based Christian Guardian was the official Methodist publication for Methodists in the prairies meant that western Methodists (students included) were getting a steady diet of pro-empire, Ontario loyalist perspectives.

48. Dr. Kilpatrick, “The Victorian Era,” Vox Wesleyana, November 1899, 19-26.

49. “Our War,” Vox Wesleyana, October 1899, 3.

50. Vox Wesleyana, February 1900, 73.

51. In The Sense of Power Berger identifies this conviction regarding the providential establishment of Empire, with its concomitant mission. He writes “The sense of mission, then, grew out of this conception of the immanence of God in the world: history has not accidentally placed millions of the ‘weaker races’ under the protection of the Empire, nor was the evolution toward a stronger union a fortuitous and fitful process. The main justification for imperial power was work directed toward the Christianization and civilization of these races.” See Berger Sense of Power, 226.

52. “Behind its popular facade, the imperialist movement cloaked a welter of conflicting, often self-serving motives and aspirations. It thrived on ambiguity and served as a united appeal for many of the era’s fashionable ideas, including the social gospel, nativism, social darwinism, and racialism.” Miller, Painting the Map Red, 4. As for the British race, many assumed that it had shown over the past few centuries its superiority. As the prominent Canadian imperialist George R. Parkin argued, one aspect of this superiority was the British ability to govern: a “special capacity for political organization may, without race vanity, be fairly claimed for Anglo-Saxon people.” See George R. Parkin, Imperial Federation: The Problem of National Unity (London: MacMillan and Co., 1892), 1. Geography was considered to contribute to the making of a superior race, for the cold northern climate brought about a process of natural selection. Consequently, the “northern races” (which included Britain, and especially Canada) were superior to the “southern races” and had a responsibility to assist the weaker races. For comments on this aspect of imperial sentiment, see Carl Berger, “Canadian Nationalism,” in Interpreting Canada’s Past, ed. J. M. Bumsted (Toronto/New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 220-228; Page, Boer War and Canadian Imperialism, 6-7.

53. Richard Allen, The Social Passion: Religion and Social Reform in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971), 10. See also, Brian Clarke, “English-Speaking Canada from 1854,” in A Concise History of Christianity in Canada, eds. Terrence Murphy and Roberto Perin (Toronto/Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 325; Semple, The Lord’s Dominion, 350.

54. Kirkconnell, The Golden Jubilee, 9.

55. Myra Rutherdale, Women and the White Man’s God: Gender and Race in the Canadian Mission Field (Vancouver/Toronto: UBC Press, 2002), 152-153. See also Mariana Valverde, The Age of Light, Soap and Water: Moral Reform in English Canada, 1885-1925 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, Inc., 1991), ch.5.

56. See chapter on “the orientals” in J. S. Woodworth, Strangers Within Our Gates (Toronto: F. C. Stephenson, 1909).

57. F. W. Osborne, “The Duties of Citizenship,” Vox Wesleyana, March 1897, 387-38.

58. “Our War,” Vox Wesleyana, October 1899, 3.

59. “Gordon’s Revenge,” Vox Wesleyana, February 1899, 4.

60. John A. Hobson is an example of one critic at the height of Empire. Edward Said is an example of a contemporary critic of western imperialism. There are a myriad number of other post-colonial critics of empire.

61. For example, see Niall Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power (New York: Basic Books, 2003).

62. Heath claims this in regards to the Boer war, and Grant claims this in regards to the First World War. See Heath, “A War With a Silver Lining,” and Grant, The Church in the Canadian Era, 114.

63. For a detailed examination of the Canadian Protestant Churches’ reaction to the death of Queen Victoria, see Gordon L. Heath, “Were We in the Habit of Deifying Monarchs ¼,” A Brief Look at Canadian English Protestants and the Death of Queen Victoria, 1901 (under review).

64. “Queen Victoria,” Christian Guardian, 30 January 1901, 66.

65. “The Death of Queen Victoria,” Canadian Baptist, 24 January 1901, 8; “Death of the Queen,” Canadian Baptist, 24 January 1901, 8; “The Queen,” Religious Intelligencer, 23 January 1901, 4; “The Queen,” Messenger and Visitor, 23 January 1901, 4; “The Queen’s Death,” Messenger and Visitor, 30 January 1901, 1; “Queen Victoria,” Messenger and Visitor, 30 January 1901, 4; Free Baptist Banner, February 1901, 36; “Our Good and Great Queen,” Canadian Church Magazine and Missionary News, March 1901, 1; “Our Lamented Queen,” Foreign Missionary Tidings, March 1901, 230; Canadian Churchman, 31 January 1901, 67-72; “Queen Victoria,” Parish and Home, March 1901, 1; “To Our Queen,” Quebec Diocesan Gazette, February 1901, 1; Letter Leaflet, February 1901, 109; “Queen Victoria Dead,” Algoma Missionary News, February 1901, 2; Palm Branch, March 1901, 4; “The Death of the Queen,” Canadian Churchman, 14 February 1901, 99; “Queen Victoria,” Trinity University Review, February 1901, 21; “The Death of the Queen,” Wesleyan, 23 January 1901, 4; “Queen Victoria,” Wesleyan, 30 January 1901, 1; “The Passing of the Queen,” Westminster, 26 January 1901, 99-100; “In Memoriam,” Presbyterian Record, February 1901, 49-50; “Queen Victoria,” Presbyterian Witness, 26 January 1901, 28; “Our Late Queen,” Presbyterian College Journal, February 1901, 339-340; Onward, 23 February 1901, 26 (reprinted from the Montreal Star).

66. And as far north as the British colony of Newfoundland. See “January 22nd, 1901,” Diocesan Magazine, February 1901, 1.

67. For a description of the event, see Vox Wesleyana, February 1901, 95; Bedford, The University of Winnipeg, 48.

68. For a discussion of other poems published in the denominational press at her death, see Gordon L. Heath, “Passion for Empire: War Poetry Published in the Canadian English Protestant Press, 1899 - 1902,” Literature and Theology 16 (June 2002): 133-135.

69. F. H. T., “Victoria!” Vox Wesleyana, January 1901, title page.

70. “Our Queen is Dead,” Vox Wesleyana, January 1901, 63.

71. “Her Character,” Vox Wesleyana, January 1901, 64.

72. “Our Queen is Dead,” Vox Wesleyana, January 1901, 63.

73. “The Throne Today,” Vox Wesleyana, January 1901, 64.

74. “The Royal Visit,” Vox Wesleyana, October 1901, 2.

75. Jones, “‘His Dominion’?,” 83-88.

76. “Pulpit and religious press combined to galvanize public support for the nation which Protestants believed would become “His Dominion.” The idea of Canada as “His Dominion” sparked the Protestant imagination and provided symbolic coherence for a broadly-based consensus. It expressed a determination to establish the Kingdom of God in the new country and became a way of articulating a mission for the nation. In more concrete terms, “His Dominion” found practical expression in a variety of ways – among them missionary activities, reform movements, and voluntary societies.” See Airhart, “Ordering a New Nation and Reordering Protestantism, 1867-1914,” 99.

77. Desmond Morton, A Military History of Canada (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1999), 117.

78. For further comments on the need to understand conceptions of Canadian nationalism within a particular time period see David A. Nock, “Patriotism and Patriarchs: Anglican Archbishops and Canadianization,” Canadian Ethnic Studies 14 (1982): 79-94.

79. Anonymous, “Canada to England,” Vox Wesleyana, October 1899, 5-6.

80. As Berger notes: “Like Bennett, Parkin and Grant made the realization of Canadian nationhood contingent upon the acceptance of racial responsibility and fulfillment of the mission. Mission was fundamental to the manner in which they conceived of nationality. Canada, they said, could only be a nation if she acted and functioned like one, and, to them, this meant that she must assume her share of the civilizing work within the Empire and be ready to defend that agency of progress.” See Berger, The Sense of Power, 231.

81. As Berger notes, “But it was not only isolationism that made imperialism suspect in Quebec; it was also another variety of mission. By the late nineteenth century the belief that French Canadians had a messianic duty to preserve the purity of Catholicism and to stand as exemplars of the true faith in North America had gained universal support among the clergy and the people. A sense of patriotism which centred upon the exaltation of Catholicism could not but find dangerous and disquieting a sense of patriotism which was rooted in the Protestant mission. Yet for both the French-Canadian nationalists and the English-Canadian imperialists, history had ordained a special avocation, and nationalism was consecrated by the hand of God.” See Berger, The Sense of Power, 232. See also Jean-Charles Falardeau, “The Role of the Church in French Canada,” in French-Canadian Society, M. Rioux and Y. Martins, eds. (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1964).

82. Sean Mills, “‘Preach the World.’” N. K. Clifford outlines some of the domestic threats that “threatened” the Protestant vision for Canada, and how domestic mission work was, in part, a response to these threats. See N. K. Clifford, “His Dominion: a Vision in Crisis,” Studies in Religion (1973): 315-326.

83. Thomas D. Brown, “The South African War,” Vox Wesleyana, January 1900, 59-61.

84. Anonymous, “Canada to England,” Vox Wesleyana, October 1899, 6 (underlining added).

85. Jonathan F. Vance, Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning, and the First World War (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997), 266-267.

Page revised: 11 January 2011