by C. J. Taylor

Parks Canada, Calgary

Number 44, Autumn / Winter 2002-2003

|

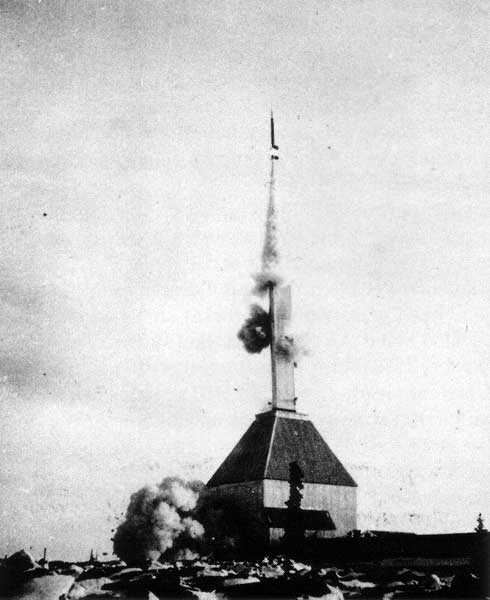

Rocket launch, Churchill Research Centre.

Source: Canadian Space Agency

A combination of geographical circumstances has given Churchill, Manitoba a long tradition of scientific research into geographical and geophysical subjects: its accessibility on Hudson Bay at the mouth of the Churchill River, and its proximity to Arctic regions and the magnetic pole. The establishment of Prince of Wales’s Fort provided an ideal base for William Wales and Joseph Dymond to observe the transit of Venus across the sun in 1769. In the mid-20th century, these geographical circumstances plus the presence of a port facility, rail head and military base at Churchill encouraged the establishment of an upper atmosphere research facility. From 1956 until the mid 1980s, this was Canada’s premier upper atmosphere research facility. It was connected with the developing space programs of the National Research Council and a number of Canadian universities. It played a central role in the development of Canadian rocketry, in particular the development of the Black Brant rocket. Moreover, the Churchill Research Range is associated with a period of great optimism for the development of Canada’s north, forming part of a climate of optimism for northern research and Canada’s role in the new frontier.

The Churchill Research Range was born out of an international endeavour in geophysical research called International Geophysical Year. IGY, in turn, developed out of a long history of scientific interest in the terrestrial and atmospheric properties of the polar regions. By the end of the 17th century it was known that the earth possessed a magnetic field organized around north and south magnetic poles. Besides being of obvious interest to navigators, it was also discovered that terrestrial magnetism was connected to weather patterns. Magnetism and the atmosphere were recognized as interacting in the phenomena associated with the polar regions known as the aurora borealis in the north and the aurora australis in the south. A comprehensive study of the geophysics of the polar regions was carried out during 1882-1883 in an exercise called International Polar Year. Eleven countries established temporary stations at arctic and sub-arctic camps to take coordinated readings of the weather, atmospheric and magnetic phenomena. Bases were established in Canada by an American expedition on Ellesmere Island, a German team on Baffin Island, and a British group at Fort Rae on Great Slave Lake. IPY was a tremendous achievement in coordinated scientific endeavour and led to the discovery of a belt of intense auroral activity across the southern arctic, from Alaska to Hudson Bay. [2] Its success inspired a second cooperative venture to commemorate its 50th anniversary, Second International Polar Year, held in 1932-1933. This time Canadian scientists participated and the Canadian Meteorological Service established arctic stations at Chesterfield Inlet and Advance on Ungava Bay in Quebec. IPY-2 was so successful that scientists began talking about repeating the venture, not in 50, but in 25 years. This suggestion was endorsed by the International Council of Scientific Unions although it was considered more expedient not to confine research to the polar regions. Accordingly, the 18 month period from July 1957 to December 1958 was designated International Geophysical Year. Over 30,000 scientists and observers from 70 countries participated. Midway through the program it was decided to continue into 1959 through another program termed International Geophysical Co-operation (IGC-59) although this 12 month extension is now considered as part of IGY. [3]

While IGY accumulated data in areas studied during first and second international polar years, it opened up new areas of geophysical research, namely the ocean and upper atmosphere. The earth’s atmosphere is comprised of distinct layers, each with particular properties. The main component of the upper atmosphere is the outermost layer known as the ionosphere extending from about 90 to 320 kilometres above the surface of the earth. Beyond that is the vast nothingness known as space although more recently radiation belts have been discovered girding the atmosphere. The properties of the ionosphere were largely unknown in the early 1950s when IGY was being planned although it was suspected that complex relationships existed between the atmosphere and the earth’s magnetic field.

Mission control console in the blockhouse, Churchill Research Range.

Source: Canadian Space Agency

Interest in the upper atmosphere was spurred by the availability of technology enabling scientists to make direct observations. Prior to World War II, knowledge of the upper atmosphere was largely restricted to indirect observations made on or near the ground. The maximum altitude that balloons could reach was about 100 kilometres. Then in 1946 a captured V-2 rocket was fired from the White Sands, New Mexico proving grounds carrying instruments into the ionosphere. During the ensuing decade sounding rockets were developed which could attain altitudes of 370 kilometres. [4] As a result of these developments, IGY planned an extensive rocket program to probe the upper atmosphere and beyond. Several hundred rockets were fired during IGY. Data retrieved from the rocket program provided new information about meteorology, atmospheric structure, ionosphere physics, aurora and airglow. Moreover, both the USSR and the USA undertook to develop space satellites to record data while orbiting the earth. Sputnik was launched by the USSR in 1957 and the following year the USA launched a satellite and fired a space probe. The space age had begun.

In North America at this time, rocket research was almost wholly carried out by the United States; Canada had little interest in this field. Consequently, Canadian scientists made no plans to participate in upper atmosphere research during IGY and confined themselves to ground based data recording. The Americans, on the other hand, planned an extensive rocket program and formed the Upper Atmosphere Rocket Research Panel (UARRP) to coordinate scientific testing. In 1954 a committee of this panel scouted possible rocket launching sites on the continent. Scientists were drawn to the Churchill area because it was in a zone of auroral activity, it lay near the magnetic pole, the atmosphere was relatively thin at this latitude, and there was a military base nearby that could provide logistical support. The locale was conveniently reached by air, sea and rail. The special committee visited Churchill in December 1954 and recommended building a rocket research facility there. [5] The United States Government, which was backing UARRP, then obtained permission from the Canadian Government before authorizing its Army Ordinance Corps to draw up plans for launching pads and ancillary buildings. [6] Technical support was to be provided by scientists of the Canadian Defence Research Northern Laboratory at nearby Fort Churchill. Both Canadian and American military units were to provide further support. [7]

The presence of the military establishment at Fort Churchill was a key element in the selection of the site as a rocket facility. The base not only provided logistical support—accommodation, services and so forth—but provided an ongoing link between the research facility and the military. It was the US military establishment that allowed the research facility to continue operating beyond the end of IGY in 1959. The United States Army built the base and operated it during the first years of its existence. Subsequently, it was taken over by the United States Air Force which had responsibility for its operation until it was transferred to Canadian civilian control in 1968. In part, this connection was due to convenience—the military had the organization and personnel necessary for mounting a rocket program—but it had a more particular cause of military interest in rockets and high altitude research that made the rocket range at least in part a military concern. This link to the military ties the range to the history of Fort Churchill and to the broader context of northern research in the 1950s.

The town of Churchill was established when the Hudson Bay Railway was extended to the shores of Hudson Bay in 1931. This provided an ocean port to the prairie provinces and it was hoped that Churchill would develop as an important shipping centre. In 1942 the US Army selected Churchill as a stop on a planned air evacuation route from Europe called the Crimson staging route and a base was established that could provide temporary medical care to wounded soldiers en route back to the US. As it happened, the facility was not needed and it was turned over to the Canadian government in 1944. The Canadian army carried out arctic training exercises from the base here in 1945-1946 and came to appreciate the attributes of the area for arctic research and training. [8] Well served by transportation routes, Churchill lay near both the northern tree line and the barrens, encouraging the army to establish a permanent facility near the town which it named Fort Churchill. Construction of permanent buildings was carried out during the summer of 1948 and shortly afterward a substantial military installation was in operation, complete with large air field, hospital, houses, offices and storage buildings.

By the end of World War II the military situation had shifted dramatically The enemy was now the Soviet Union and the North American allies organized for a perceived threat of attack from the north. During the Cold War, the nature of the imagined assault changed, from infantry invasion to bomber attack, but Canadian policy regarding defence of the north remained rooted in its alliance with the United States, the ability of Canadian troops to carry out northern operations, and the economic development of the north. Fort Churchill was developed to implement this strategy. It was never a strategic site as such, although it could function as a staging area for airborne infantry. Its principal function was as a base for arctic research and testing for Canadian and American military material. The military establishment further encouraged the development of a strategic northern community. In this capacity Fort Churchill played an important role until its abandonment by the military in 1964. [9] In 1947 the United States Army based its First Army Test Detachment here and the Canadian Defence Research Board established its northern laboratory. Subsequently, Fort Churchill emerged as an important research centre for cold weather testing of men and equipment for both the Canadian and American military. [10]

Aerial view of Fort Churchill, circa 1960.

Source: Canadian Space Agency

It was not long before rocket trials were being carried out at Fort Churchill. Rockets formed an important part of the arsenal of any army of the 1950s and they were considered key to air defence. How well surface to air missiles could perform in arctic conditions was an obvious concern and defensive short-range guided missile firings were carried out at Fort Churchill under joint Canadian-United States army auspices from 1954 until 1956. A Canadian unit, the Royal Canadian Artillery Guided Missiles Trial Troop, participated in these tests. Meanwhile, a more awesome use of rockets was being contemplated. By the mid-1950s, both the United States Air Force and its Soviet counterpart were developing long range guided missiles that could be fired over the pole to designated targets. Travelling at high altitude, these rockets were guided by sophisticated electronic systems that used radio waves to follow programmed routes. A problem was that the atmosphere of the arctic was infamous for its unpredictability as geomagnetism and auroral displays played havoc with radio communication and navigational instruments. By 1954, then, the United States military establishment would have been keenly interested in understanding more about the properties of the upper atmosphere above the arctic. [11]

Telemetry room, Churchill Research Range.

Source: Canadian Space Agency

Construction of the rocket research facility was largely completed in the summer of 1956 by US Army engineers and a civilian contractor. The original complex comprised a row of buildings linked by an above ground tunnel. It comprised a blockhouse, preparation buildings and rocket launchers. Because it was necessary to keep the rockets poised and primed for launching for up to several hours awaiting the right atmospheric conditions, the launching pads were enclosed by corrugated steel walls that allowed the rockets to be kept warm. Moments prior to blast off, doors at the base of the launch building would be opened so that the shock of the blast would be quickly dissipated. The US Ordnance Corps operated the range until 1961 with about 175 personnel. [12] They manned the communications network, flew the helicopters which retrieved the rocket nose cones and provided support services.

The first vehicle fired from the new facility was probably a Nike-Cajun two-stage rocket launched on behalf of the United States Air Force and the University of Michigan in October 1956. [13] This rocket was used to test the facilities and take atmospheric readings. The major portion of the American IGY rocket program was conducted at the Churchill Research Range. Rockets were fired during periods of sunspot activity, into auroral displays as well as the quiet arctic night and collected data from a variety of altitudes. The sounding rocket program permitted the detection of x-rays and auroral particles high above the earth and measurements were taken of winds and temperatures, cosmic rays and magnetic fields. IGY sounding rockets enabled a number of discoveries. It was found, for example, that the temperature of the atmosphere 100 kilometres above Churchill could reach almost 2,000 degrees centigrade compared to almost 1,000 degrees at the same altitude above White Sands, New Mexico. [14]

The success achieved in the fields of upper atmosphere and space research during IGY inspired greater non-military initiatives. National and international organizations dedicated to furthering scientific exploration of the ionosphere and beyond grew directly from IGY. The Special Committee for Space Research (COSPAR) continued and extended cooperative studies of space initiated by IGY. Two new US agencies, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), were formed during the IGY program. With the declaration of IGC-59, the United States Defence Department joined with NASA in an experimental rocket program and allocated funds to permit the continued operation of the Churchill range. [15] November 16-22 of that year was designated International Rocket Week and two Nike-Cajun rockets were fired from Churchill to measure water vapour in the upper atmosphere and conduct tests on the earth’s magnetic field.

By 1959 Canadian scientists were actively participating in upper atmosphere research and a number of agencies organized research and development in this field. The Churchill became an important centre for the Canadians as well as the American rocket programs In November 1958 the Canadian Armaments Research and Development Establishment (CARDE) launched a Nike-Cajun rocket to carry out experiments in the earth’s hydroxyl layer. [16] CARDE was also engaged in developing a solid fuel rocket propellant. Non-military rocket research was organized under the aegis of the National Research Council. In 1959 the NRC formed the Associate Committee of Space Research headed by Dr. D. C. Rose. This committee participated in international agencies and coordinated civilian rocket launchings at Churchill. [17]

The most tangible sign that Canada had entered the realm of rocket research was the development in 1959 of the Black Brant, the first rocket designed and built in Canada. Initial design work was done by CARDE at its Valcartier laboratories but the engineering was done by Bristol AeroIndustries of Winnipeg. [18] Testing was done at the Churchill Research Range and the first Black Brant was launched from there in October 1959. That year CARDE improved the design and Black Brant II was launched in 1960, achieving an altitude of 150 kilometres. Complete engineering control of the program was then turned over to Bristol which had built a manufacturing plant north of Winnipeg. Since then, the Black Brant has continued to be refined and improved and has been mated to various types of boosters to take bigger payloads to higher altitudes. The Black Brant XII recently developed by NASA and Bristol, has an estimated range of 1600 kilometres. [19] It has earned an international reputation and even after the closure of the Churchill facility, Black Brants are the principal sounding rocket of NASA.

The development of Canadian interest in sounding rockets and upper atmosphere research led to greater Canadian participation in the management of the Churchill Research Range. At the end of 1959 a Canadian-United States Operating Coordinating Group was formed to manage the range. Its mandate, set forth in February 1960 described its responsibilities as being: “to coordinate the upper atmosphere rocket research programme, to coordinate the scheduling [of this programme] with the scheduling of the engineer-user environmental missile tests of the armies of Canada and the United States at Fort Churchill ...” [20] Practically speaking, the Americans were prepared to launch 20 rockets a year for Canada. Half of these would be for the Defence Research Board, the other half for a university rocket program coordinated by the National Research Council. [21] The Operational Coordinating Group remained the governing body of the range although day to day operations were handled by other agencies and funding bankrolled by the United States military.

Despite growing Canadian involvement, activities at the Churchill range were quiet during 1960 and in February 1961 a fire destroyed most of the buildings at the range head forcing its closure for the rest of that year. At the same time, the US Army Ordnance Corps, which ran the facility, was planning to withdraw, leaving open the question of who would manage the facility. Negotiations between Canada and the United States and the various agencies of the American defence and space research establishments lasted into 1962. In July 1962 responsibility for managing the Churchill range was transferred to the United Stated States Air Force Office of Aerospace Research (USAF OAR) which oversaw the rebuilding of the facility. The USAF had moved into space research in a big way, directly involved with military research and indirectly in civilian research through its Goddard Space Flight Centre which financed many university sounding rocket campaigns.

At the time of the USAF takeover, the facilities were described as being very meagre and in an advanced state of disrepair but the air force moved quickly to improve the range. [22] Plans were drawn up by the air force and the army corps of engineers and contracts were let for the construction of new buildings over the next two years that would greatly improve the facilities. By 1964 there were four launching pads designated Nike-Cajun, Aerobee, Universal and Black Brant. The launching facilities were greatly improved. A new blockhouse constructed of reinforced concrete served as the nerve centre for the complex and connected the four launching areas. A sprawling operations building was constructed to house such facilities as instrumentation, communications and transmitting and receiving equipment. Staff amenities such as bunks and a canteen were also included. The Universal launcher had a pitched roof which could cantilever open to allow the rocket to be fired from inside the building. Improved heating arrangements allowed scientists to work in a shirt-sleeve environment even when outside temperatures reached below minus 40 degrees centigrade. The air force developed a clam-like envelope that could keep rockets being held in a firing position from freezing. Because rapidly changing wind patterns made the aiming of rockets problematic, it was often necessary to change the elevation of the rocket during the countdown. In order to accomplish this change of setting in the minimum amount of time, the two largest launchers were equipped so that the mechanism for setting the trajectory could be operated by remote control from the blockhouse.

Rocket being launched from the Aerobee Launcher, Churchill Research Range.

Source: Canadian Space Agency

Fort Churchill was still relied upon for logistical support, providing an operational centre for the range, lodging for permanent and temporary personnel and the technical support of the Defence Research Northern Laboratory. The range itself was operated by Pan American Airways under contract to the USAF. By the terms of a Canada-United States agreement, however, just under 75 per cent of the contractor’s employees were to be Canadian. When the range formally re-opened in November 1962, there were 154 Pan Am employees at the range plus a complement of about 18 USAF officers and men. By 1964 there were about 200 personnel connected with the range. [23]

Preparing a Black Brant rocket for launch, Churchill Research Range.

Source: Canadian Space Agency

The first scientific rocket launched from the refurbished facility conducted an experiment for the Goddard Space Flight Centre which involved firing sodium vapour grenades from the rocket after it had penetrated the upper atmosphere to measure wind velocity at that altitude. [24] A major rocket campaign was initiated in 1963 called Operation Probe High which performed experiments to measure the effects of the solar eclipse on phenomena such as cosmic rays. Canadian universities became active in upper atmosphere research in this period and during 1963 the universities of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Western Ontario conducted ionospheric experiments using rockets fired from the Churchill range. [25] During 1964 and 1965, rocket campaigns were carried out from Churchill to participate in the research program of the International Year of the Quiet Sun, a follow up to IGY which had taken place at a time of high sunspot activity. By December 1965 the USAF OAR had supervised the launching of about 315 sounding rockets and 150 research balloons from the Churchill range for a variety of clients. [26]

By 1965 military interest in Churchill was on the wane. The United States military was waging war in Vietnam. The newly formed state of Alaska was able to place pressure on the US military establishment to move its cold weather testing facilities there and the newly elected government in Ottawa moved to curtail the expenses of Canada’s military. For these and other reasons Fort Churchill was closed in 1964. While the closure of the base had an indirect effect on the research range, the military also began to reduce its direct involvement in the facility. The American war machine was less interested in funding esoteric high altitude tests from the Churchill facility. All of these factors had an impact on the research range.

Fortunately, 1965 was a period of growth and maturity for the National Research Council which took up some of the slack created by the withdrawal of American support. By this time, the NRC was coordinating a significant program of rocket and other space research in Canada. A range of experiments had been conducted by its own pure physics laboratory and a half dozen universities. During 1964-65 the NRC supervised five rocket experiments at Churchill to obtain data that would complement those being obtained by Canada’s Alouette satellite. [27] In the spring of 1965 the NRC formed the Churchill Research Branch to better coordinate these rocket experiments and that summer the University of Saskatchewan established a Space Engineering division with NRC support. [28] The development of a Canadian civilian sounding rocket program culminated in the establishment of the NRC’s Space Research Facilities Branch toward the end of 1965. At this point, Canada was able to assume greater responsibility for the Churchill Research Range and at the end of 1965 the NRC Space Research Facilities Branch replaced the USAF OAR as the manager of the facility. Overall operations were still governed by the Joint Operational Coordinating Group, however, and the running of the range was left to Pan American Airways acting as a contractor to the NRC. Nonetheless, the transfer of the Churchill range from the USAF to the NRC marked the beginning of a new phase in the history of the range and a greater maturity in the Canadian scientific establishment.

With both NRC and NASA support, the Churchill research Range flourished as a sounding rocket facility, becoming an international centre for upper atmosphere research. In this period, scientists favoured rockets as a relatively cheap and efficient way to gather data from the upper atmosphere and even space. Satellites, by contrast, took years of advance preparation and access was usually restricted to all but the most affluent of researchers. NRC and NASA grants further encouraged university research projects to utilize the Churchill facility. As a result, the rocket range continued to be a busy place through the 1960s. An Australian scientist involved with the American rocket program described the range as “the mecca for auroral scientists at this time.” [29] The later 1960s marked the zenith for rocket research as subsequently the American military based its rocket experiments in Alaska and NASA began to place more emphasis on its manned space programs.

In 1970 NASA stopped contributing to the upkeep of the range although the joint coordinating group still maintained nominal jurisdiction over the operation. It is a measure of the independence of the Canadian rocket program that the NRC could still maintain the Churchill operation on its own. Changes in the operation were effected, however, as the Space Research Facilities Branch sought to rationalize its administration. The resident staff at the range was reduced to between 50 and 60 at the end of 1970 and subsequently the base of logistical support was moved to Gimli. [30] In 1978 the operation of the range was given to a Canadian contractor, Andre Denis Garneau and Associates.

A number of important rocket campaigns were carried out at Churchill during the 1970s and 1980s. While ionospheric testing in conjunction with satellite recording continued throughout this period, a special program was initiated in 1975 as part of the International Magnetospheric Study. [31] In 1974 and 1975 two American balloon programs were carried out at the facility. One of the most ambitious experiments carried out from Churchill was Project Waterhole conducted between 1980 and 1985. This entailed sending rockets through auroral displays to an altitude of about 300 kilometres and then detonating a bomb in the nosecone to cause a chemical reaction that would douse a portion of the aurora borealis with water vapour. [32] The experiment was designed to find out what supplies the enormous electrical power of the aurora borealis. Another rocket campaign was carried out in 1984 as part of an international ionospheric study. But activity at the Churchill research Range diminished as emphasis was placed on other aspects of the Canadian space program and the facility was closed down in 1985.

The immediate reason for the sudden abandonment of the Churchill facility was the federal government’s new financial policy, announced in 1984, which greatly reduced the budget of the NRC and forced it to make drastic program cuts. [33] But a change in science policy made in the 1970s had given rocket research a low priority in the larger space program. The 1974 report of the president noted a redefined role for the NRC: future research would be tied to economic development, pure research would be given a diminished priority. [34] As sounding rocket research was associated with pure science, not industrial development, it became a poor stepsister to other more glamourous aspects of the Canadian space program such as participation in the NASA space shuttle program. This situation was confirmed in a policy statement of the Ministry of State for Science and Technology written in 1981. Space policy for the 1980s, it noted, was rooted in a larger industrial strategy for the development of high technology industries. [35] Accordingly, emphasis was placed on activities which could encourage Canadian manufacturing and projects such as the development of Canadarm and satellite communications and mapping overshadowed more venerable activities like ionosphere research. So long as the space program was well funded, it could afford to carry activities not wholly connected with the objectives of promoting high tech research and development. But when the budget was slashed, the rocket program had to be jettisoned.

Since 1985 there have been short lived attempts to reopen the site. In 1988 NASA carried out four launches from the site. In 1989 the Local Government District of Churchill and the Churchill Chamber of Commerce encouraged the formation of a special committee to seek ways and means to reopen the range on a commercial basis. As a result of this initiative, Akjuit Aerospace was formed in 1992 to operate the range. After carrying out some limited development of the site, Akjuit Arrospace, shut down because of lack of funds. Despite this setback, the Town of Churchill would still like to open the facility. Meanwhile, the Churchill Northern Studies Centre, established to provide a base of logistical and technical support for Canadian university northern research programs, took over the range’s old operations building. The Northern Studies Centre is interested in many things but sounding rockets do not fall within its mandate. As a result, part of the original facility has fallen away to be re-adapted for future new uses. The rest of the facilities remains in a kind of mothballed limbo. A possible future role is that of tourist attraction. In 1988 the range was recommended as being of national historic significance by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada and a plaque commemorating the site was unveiled in 2001.

1. The author is grateful for assistance provided by the Facilities Branch of the Canada Centre for Space Science and the Directorate of History at the Department of National Defence. He also wishes to thank Mr. William Erickson of Churchill for information regarding the history of the facility.

2. C. J. Taylor, “First International Polar Year, 1882-83,” Arctic, xxxiv, 4 (Dec. 1981), 376.

3. Encyclopaedia Britannica, (1966) vol. 12, s.v. “International Geophysical Year.”

4. Encyclopaedia Britannia Micropedia (1980), vol. 15, “Rockets and Missile Systems.”

5. Special Committee for the International Geophysical Year of the Upper Atmosphere Rocket Research Panel, Proposes Rocket Launching Site at Fort Churchill, Washington, D.C., 21 Dec. 1954.

6. Department of National Defence, Directorate of History [hereafter DND], file S-8931-5-P2, draft memorandum to Cabinet on Fort Churchill Rocket Range, Oct. 1959.

7. A. E. Coney, “The IGY Year,” in Defence Research Northern Laboratory 1947-1965, compiled by A.M. Pennie (Ottawa: Defence Research Board, 1966), 98.

8. An order-in-council dated October 1946 authorized an establishment at Fort churchill “for the purpose of conducting year round trials of sevice and equipment under conditions representative of northern Canada at Churchill Manitoba.” Cited in DND, file S-8931-5-P2, draft memorandum to cabinet, Oct. 1959.

9. R. J. Sutherland, “The Strategic Significance of the Canadian Arctic,” in The Arctic Frontier, ed. By R. St. J. Macdonald (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966), 263.

10. D. J. Goodspeed, A History of the Defence Research Board of Canada (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1958), 181-82.

11. “Electronic guidance problems may be somewhat alleviated when the aforementioned knowledge of the shape and magnitude of the earth’s magnetic field at high altitude is gathered at many different latitudes where the filed changes rapidly with change in altitude.” Robert F. Phillips, The Churchill Research Range: a history of its acquisition and management by the Air Force (Washington, D.C.: Office of Aerospace Research, 1964), 2.

13. National Research Council [hereafter NRC], Canada Centre for Space Science, Facilities Branch, Record of Launchings Conducted at Churchill Research Range.

14. Encyclopaedia Britannica (1966), vol. 12, “International Geophysical Year.”

15. DND, file S-8931-5-P2, draft memorandum to Cabinet on Fort Churchill Rocket Range, Oct. 1959.

16. NRC, Canada Centre for Space Science, Record of Launchings Conducted at Churchill Research Range.

17. Wilfrid Eggleston, National Research in Canada: The NRC 1916-1966 (Toronto: Clarke, Irwin 8rCo., 1978) 419.

18. Clifford Cunningham and Peter Jedicke, “Canada’s ‘Black Brant’ Rockets,” Spaceflight, Jan. 1987.

19. Joel W. Powell, “Black Brant X - A Canadian Export,” Spaceflight, Jan. 1987.

20. DND, file S-8931-5-P2, “Proposed terms of reference for the Canada-United States Operational Coordinating Group for the Rocket Research Facility,” Feb. 1960.

21. Wilfrid Eggleston, National Research in Canada, 419.

22. Robert F. Phillips, The Churchill Research Range, 59.

23. Robert F. Phillips, The Churchill Research Range, 32.

24. Robert F. Phillips, The Churchill Research Range, 45.

25. NRC, Canada Centre for Space Science, Record of Launchings Conducted at Churchill Research Range.

26. NRC, press kit on the National Research Council’s Churchill Research Range, Jan. 1966.

27. NRC, Report of the President, 1975-76, 104.

28. NRC, NRC Review, 1966, 15.

29. Robert H. Eather, Majestic Lights: The Aurora In Science, History, and the Arts, Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union, 1980, page 264.

30. NRC, Space Facilities Branch, srfb newsletter, no. 7 (15 April 1970); NRC, The Canada Centre for Space Science (Ottawa: Department of Supply and Services, 1982), 12.

31. NRC, Report of the President, 1975-76, 104.

32. NRC, Report of the President, 1979-80, 62.

33. NRC, Annual Report, 1984-85, 5.

34. NRC, Report of the President, 1974-75, “NRC 1974 - A Redefined Role,” 11.

35. Ministry of State for Science and Technology, “Background Paper No. 20: The Canadian Space Program Plan for 1982/83 - 1984/85,” Dec. 1981.

See also:

Historic Sites of Manitoba: Churchill Rocket Range (Churchill)

Page revised: 14 November 2020