Manitoba History, Number 2, 1981

|

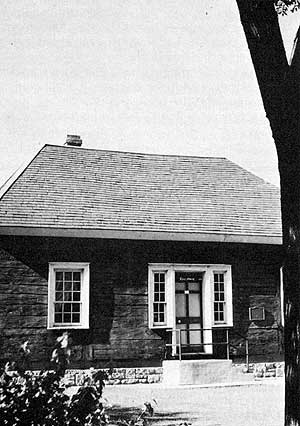

Across from Winnipeg’s CPR station, in an oasis of grand trees, nestles tiny Ross House Museum. The building, an example of Red River log construction, is the only extant vestige of a prominent Red River family.

Ross House Museum, 1955

Source: Archives of Manitoba

The Ross connection with this area began in 1825 when Alexander Ross moved his family to the riverbank colony. Ross, a native of Scotland, immigrated to Canada in 1804. In 1809, he joined with John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company and was posted to Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River. When Astor’s ambitions failed. Ross joined the North West Company in 1813 and was promoted to Chief Trader at Fort Nez Perces in 1818. [1]

Alexander Ross, who married Sarah, the daughter of an Okanagan Indian Chief, had three children by the time the Hudson’s Bay Company merged with the North Westers. Ross had grown disillusioned with the fur trader’s life, but more importantly, he was concerned with “the necessity of returning to a place where I could have the means of giving my children a Christian education.” [2] For Ross, the raison d’etre of Red River was just that: to make possible a settled and civilized life in the wilderness. [3]

In 1825, Governor Simpson, in deference to Ross’s contribution to the fur trade, granted him a large river lot two kilometres north of Upper Fort Garry. Ross, who taught school, farmed his property and established a dry goods store on his land, became a link between the company and the settlers and often negotiated between the groups on local issues.

During the year 1835, after some clamouring on the part of the colonists, the Council of Assiniboia was formed to advise the Governor of the HBC and to pass by-laws regulating the affairs of Red River. To this first legislative body in the North West, Alexander Ross, a sheriff of the colony, was appointed a councillor, an indication of membership in the elite. [4]

To house his growing family. Ross built “Colony Gardens”, a commodious Red River frame home. Besides his official duties, he worked towards establishing the first Presbyterian church in Kildonan, and wrote several books, including his informative history of The Red River Settlement. Alexander Ross was also a devoted father, and was particularly sensitive to the role of the “half-breed” progeny living around Red River. He had foreseen long in advance the problem of the stagnant and isolated economy which could not accommodate the escalating numbers of displaced Métis arriving in Red River. The buffalo hunt, that important institution of the Métis, was clearly coming to an end as the buffalo dwindled in numbers, and yet farming did not seem to be a likely alternative for these native sons and daughters. Furthermore, the French “Métis” or English and Scottish “half-breeds” represented two distinctive communities with less in common than might be expected.

Ross was determined to provide his children with the opportunity to avoid the problems faced by the mixed-blood community. His children, with the exception of James, were educated locally. William Ross, the builder of Ross House, was appointed sheriff after his father resigned the post in 1851, and was given the additional lob as first postmaster for Red River. Henrietta, a cultured and beautiful girl, married Rev. John Black of the new Kildonan parish and she remained prominent in Red River society. Mary married Rev. George Flett, the first ‘mixed-blood’ ordained as a Presbyterian minister in the west. James Ross studied law and journalism at the University of Toronto where he received a gold medal for his scholarly work. When his older brother William died, James was assigned the positions of sheriff and postmaster.

The children themselves were fully aware of their important social position. At the death of his father, James, the family spokesman, wrote home to his siblings:

we at present occupy a certain standing in the community. Owing to Papa and William—and to our connection with our worthy minister Mr. Black ... we have a certain standing and respectability, and we must keep it ... We must show ourselves worthy of that esteem by our doings. [5]

William, the second son of Alexander, was born in the Columbia River district in 1825 and brought to Red River on horseback in 1826. His formal education was entirely in the settlement. After a brief period working on the transport brigades to Pembina, he married Jemima McKenzie, also the daughter of a prominent fur trade family. To accommodate their growing family, William began to build Ross House in 1852 near the riverbank of the eastern part of the original Ross estate. A flood in 1852 delayed more than a start to the house, but by June of the following year, William complained to his brother James that although the frame of his new house was up, a shortage of wood further delayed construction. [6] His sister Margaret’s husband, Hugh Mattison of Kildonan, did much of the carpentry work, including a surviving dry sink of pine which attests to his skill as a tradesman.

The Ross family moved into their new house in early 1855. Alexander Ross declared William’s house “the prettiest in Red River” [7] built at a cost of £252. The fine home reflected William’s prominence in the settlement as the sheriff, councillor to Assiniboia, magistrate and keeper of the jail. Even Alexander Ross, who was so apprehensive about his half-breed children, had to admit that William was “in a fair way of becoming respectable”. [8]

In addition to these honours and duties, William was appointed the first postmaster to the settlement. For the grand salary of £5 a year, Ross ran the post office from his new home, making it a bustle of activity and a meeting place for local people. In his year as postmaster, Ross handled 2,912 letters. 2,437 newspapers and 580 parcels. [9] Letters were addressed simply to “Red River, British North America”.

Within two years of completing Ross House, William died on 6 May 1856. His wife was left with four children and another baby on the way. In October of that same year, old Alexander Ross joined his son in the churchyard at Kildonan. The Ross family was left without its two pillars.

In 1860, Ross’s widow Jemima married William Coldwell, a recent arrival from Ireland. Coldwell apprenticed in Dublin as a copysetter and proofreader for a newspaper and came to work for the Globe in Toronto. In Red River, he joined with William Buckingham to publish Red River’s first paper The Nor’Wester. When Buckingham left the Nor’Wester in 1860, he was replaced by James Ross, who had moved back to Red River to administer the Ross family affairs. James later joined the Globe’s staff in Toronto.

William Ross House, 1890

Source: Archives of Manitoba

In 1869, James again returned to the settlement which was in a turbulent state. He was selected to represent Kildonan in Riel’s provisional government and became “a spokesman for the English as definitely as Riel was for the French.” [10] Coldwell was certainly a partner to his brother-in-law in these dealings for the two shared a vision for the future of Red River from their Nor’Wester days.

After 1870, Coldwell edited a new paper, The Manitoban, which represented the political views of the early inhabitants of Red River. Later, he spent ten years as a parliamentary reporter for the Free Press. His obituary stated that he had been an invalid since 1889, [11] but his personal papers show this period to begin about 1885.

Although Jemima had been willed the Ross property only as long as she remained a widow, she seemed to have reached an agreement with her children which left the property more or less in her control. Son William and daughter Margaret leased a part of “Brookbank”, their name for the estate, from their mother for a nominal fee. Over the years, parts of the long river lot were parcelled off and either sold or rented by agreement between Jemima Coldwell and the Ross children. The lot that City Hall is on for example was originally part of the Ross estate. Other parcels of land were expropriated for Market Square and the Winnipeg Transfer Railway. The sale of these properties was the Coldwells’ only income in later years.

To the original Red River frame home which William Ross built, the Coldwells added a kitchen and rear porch. In the winter, they banked earth and hay against the walls in an effort to keep the house warm. In the first kitchen in the main house was the Carron stove, supplemented in winter by a coal-burning stove. As an invalid, Coldwell slept in the parlor by the stove in winter, while their children slept in the large attic to which access was through the kitchen by a set of heavy stairs held by a rope.

A cutaway section of the wall in the interior of Ross house shows its construction. Clay and lime were mixed together for the interior plaster and there is still most of the original plaster under the newer layer. The glass panes in the window, which were imported from England, eventually came to Red River by the old York Factory route. [12]

The house was covered with wood siding, probably soon after its construction in 1854, as log houses had little prestige in Red River. Massive wooden water barrels caught the run-off from the roof which supplemented the well water. The Coldwells probably also kept a barn on the property.

After the Coldwells died, the land and house were sold. Midland Construction bought the building and used it as an office for its lumber yard. The building was saved from demolition in 1947 through purchase by the City of Winnipeg and the Manitoba Historical Society. It was moved to its present site at Sir William Whyte Park across from the C.P.R. station and restored to its present state.

The museum now operates during the summer months and attracts about 300 visitors annually. Many of these people are tourists to the city, for relatively few Winnipeggers appear to know about Ross House. The House needs some major refurbishment to replace some of the massive squared logs, but it remains one of our best examples of Red River frame construction as well as a memorial to the Ross family.

1. Professor (George) Bryce “Alexander Ross—Fur Trader Author, and Philanthropist” Queen’s Quarterly, July 1903, p. 46-49.

3. W. L. Morton in the introduction to Alexander Ross’ The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress and Present State reprinted by Hurtig Publishers. Edmonton 1972, p. XV. In this view, Alexander Ross differed fundamentally from Lord Selkirk who had not foreseen the large influx of country-born people, the families of retired fur traders and their native wives. The colony ultimately came to serve both purposes.

4. A. S. Morton A History of the Canadian West to 1871 Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd. Toronto 1939, p. 667.

5. The Ross Family Papers, P.A.M. letter no. 200, 24 December 1856.

6. Ibid., letter no. 45, 28 June 1853. This shortage of wood for construction was to become chronic for the next two decades in Red River In this case. it may have been the result of a fire in 1852.

7. Ibid., letter no. 100, 25 August 1854.

9. The Original Ross House souvenir booklet of the Manitoba Historical and Scientific Society, n.d., p. 2.

10. W. D. Smith “James Ross” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Vol. X, University of Toronto Press p. 630.

11. Manitoba Free Press 19 February 1907.

12. Souvenir booklet, op. cit., p. 4.

Page revised: 19 July 2009