by Gene Walz

Film Studies Program, University of Manitoba

Manitoba History, Number 2, 1981

|

W. D. Valgardson’s short story, “God Is Not a Fish Inspector” might better be called, “The Old Man and The Lake.” It is the Gimli writer’s version of the mythic struggle between a stubborn old fisher-man and a deadly antagonist. In Valgardson’s story the fisherman is named Fusi Bergman. He’s a 70 year old man who refuses to go quietly into a rest home. Instead he gets up at 3 a.m. to catch a fish or two and to outwit the fish inspectors who have taken away his fishing permit because of his age. His antagonist, the shark equivalent, is his daughter Emma. Like Hemingway’s novella, the story’s effectiveness comes from its lean, harsh, almost abstract qualities.

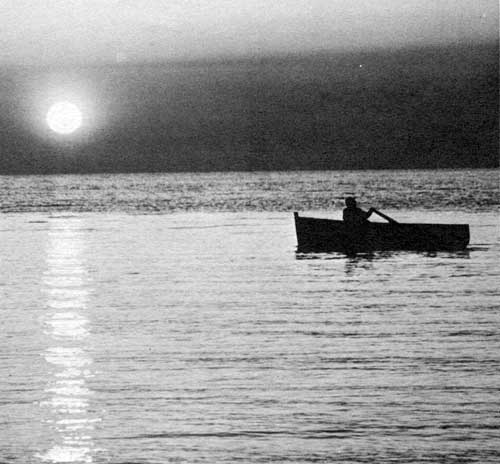

Photo by Allan Kroeker

Allan Kroeker has made not one but two films based on this story. One is an award-winning adaptation, the other a documentary about Valgardson, his story, and the Interlake region he grew up in and returns to every summer for creative sustenance. The two films, God Is Not a Fish Inspector and Waiting for Morning, make interesting companion pieces. Not only do they say something about life on Lake Winnipeg, they also reflect each other in unique ways.

“Icelanders,” the narrator in Waiting for Morning explains, “by day they played poker with the sea; in the evenings they made their escape into stories and legends of survival.” Gambling and survival are stories that all the faces in these two films tell: the man with the rebuilt plastic fingers, the men in the old photos, Fusi Bergman (as played by Ed McNamara), and W. D. Valgardson’s father, Dempsey.

This relationship is recognized in Kroeker’s documentary, but it is not harped upon. Dempsey Valgardson, the man who doesn’t need to fish, who doesn’t make enough from it to continue, but who still goes out onto the lake every fishing morning. Fusi, the man who keeps on fishing despite his years and the physical pain it causes him and despite (or maybe because of) the conflict with his daughter. The Fusi-Dempsey association is a crucial one; it gives Fish Inspector not only emotional strength but experiential intimacy (to say nothing of the Freudian dimensions). Fusi Bergman is created partly from first-hand knowledge.

Ironically, several people in the documentary, some of them Dempsey’s friends, claim that they knew the real Fusi Bergman. Yet no one recognizes any part of Dempsey in the character, and each person’s Fusi is different from the next one’s. Valgardson sees this as a function of his presentation of credible details, “The success of my fiction,” he says on camera, “is the illusion of reality that it creates.” Not necessarily. What he has created is a vivid and accessible type. Kroeker has taken this type and fleshed it out into a more convincingly real person.

The difference is not a matter of movies being inherently more believable and “realistic” than print fiction. Hardly anyone believes that anymore. Kroeker has simply used the cinematic tools at his disposal to better advantage.

Ed McNamara’s acting, for instance, is flawless. He is so comfortable in the role of Fusi, and his acting style so rich with the kinds of tics and mannerisms that we associate with a real person that it looks as if Kroeker had somehow gotten a real Gimli fisherman to act natural for the camera. When his hands shake from rage or weariness, the film has the kind of documentary feel to it that is so essential to fictional portraits yet so rarely captured on film.

McNamara is backed up by an even more persuasive piece of acting by William Seller as Jimmy Henderson, a senile and barely comprehending resident of the old folks’ home who was mentioned only briefly in the short story. It is hard to believe that Seller could be anything but a vacant, slack-jawed and immobile dotard whom Kroeker discovered and filmed rather cold-heartedly in documentary style. (Yet Seller in real life is an alert and lively actor) When Fusi puts a sweater on Jimmy and buttons it up wrong, it is one of those captivating moments that make you realize that good fiction is not a matter of Coleridge’s “willing suspension of disbelief” but of its unwilled suspension. The illusion involves you and sweeps you along regardless of your volition.

Kroeker reinforces this with a shooting and editing style that alternates nicely between strategic, detailed close-ups and longer, descriptive contextual shots. (The only thing he can be slightly faulted for here is a tendency to overlook the harshness of the story. Some location photography is postcard pretty and diminishes Fusi’s struggle. A close-up of Fusi’s hands as he painfully tries to knead some flexibility into them is relegated to Waiting for Morning but is conspicuous by its absence in Fish Inspector) Kroeker also subtly expands and alters the story to make it work better as a film. Additional dialogue and bits of action are included so seamlessly that it is obvious that the filmmaker had gotten inside the story and its main character. Doing this allowed him to eliminate the interior monologue (still used in outtakes in Waiting for Morning), thus freeing Fusi of the short story’s rather fake intellectualism and making him a more consistent experience-oriented person.

All of these strengths in a way betray Fish Inspector’s one flaw. Daughter Emma and her husband John are one-dimensional caricatures in the story, and the film does less to infuse them with enough humanity to make them satisfyingly credible than it does with Fusi and Jimmy. Scripting, casting, acting and camera placement are used to make them amusing but fake religious fanatics. As in the story, perhaps even more so because of the strengths of the other two characters, they are pawns in an artificially contrived power struggle rather than the human embodiments of that struggle.

God Is Not a Fish Inspector is otherwise so smooth and skillful a film that this flaw assumes only minor proportions. Few, if any, adaptations of Canadian stories are as stylish, substantive and emotionally involving. If Kroeker’s proposed adaptations of stories by Valgardson and other local writers are as successful as this, film could begin to assume its rightful place among the other arts on the prairies.

Page revised: 23 April 2010